Long COVID – And Its Impact on Health Care Workers

How prevalent are the lingering impacts of long COVID, and how do these impacts affect health care workers? One study found about 7% of adults have had long COVID at some point, and 3.4% presently had symptoms of long COVID. Those numbers may look small but if representative to the entire population, that is over 18 million adults. Far fewer children had long COVID -- 1% or 724,508 -- but the impacts on families may be devastating when a child suffers. Surprisingly to many, adults 35-49 were more likely than adults 65 and older to have long COVID, a group more likely to be responsible for generating a family’s income. Poorer adults, those with family incomes from 200 through 399% of the federal poverty level were just over twice as likely to ever have or currently have long COVID compared to adults with family income at 400% or higher of the federal poverty level. Finally, as yet another point of comparison, Hispanic adults were more likely than white or Black adults to have had or currently have long COVID.

The numbers above give one way of appreciating differences in rates of long COVID but, during a recent MCN learning collaborative supported by the Center for Disaster Philanthropy, we also looked in other ways. The four-part series, "Understanding COVID-19 Impacts and Promoting Well-Being of Community Outreach Workers in Underserved Communities,” was developed by Kaethe Weingarten, PhD the Director of MCN’s Witness to Witness Program (W2W) and delivered by three W2W faculty, Patricia Navarro, LMFT, Pamela Secada-Sayles, MPH, and Jessica Calderón-Gomez. Throughout the series, we reviewed what specific structural conditions of people’s lives make certain groups, as noted above, more vulnerable than others to contracting COVID-19 and then to effects of COVID-19.

For instance, farmworkers may have difficulty isolating when they have COVID-19 if they live in congregate housing, or they may not be able to access medical care if they live in a rural community that is distant from a health center. Further, should they have symptoms of fatigue months after the initial infection, they are unlikely to be able to follow the four P’s advice suggested by some Long COVID centers: Plan to be active during the time of day you have the most energy; Pace yourself; Prioritize only that which must be done or that gives you pleasure; Assume the Position when doing tasks that conserves the most energy.

In sum, people with long COVID have diminished capacity to live their lives as they did before their infection. The psychological impact on any individual, child, or adult, of no longer having the energy to behave the way they prefer, is considerable. In our learning collaborative, the term we use for that experience is self-loss and the term immediately resonated with participants. One member of the learning collaborative had this to say about that experience: “Our discussion on self-loss helped us see the reality that individuals dealing with COVID or long COVID face a real change in their ability to live their lives as they once did”.

But long COVID does not just affect the individual with the diagnosis. For every person with an experience of self-loss there is a corresponding experience for those who know, work, and live with that person and our term for that is “other-loss.” When a health care practitioner, for example, interacts with someone who has little energy to participate in life as they did before, it has an impact. One participant had this to say about the experience of other-loss: “We all have experienced adjusting to the aftermath of COVID. This learning collaborative provided us with a new perspective on navigating the change we see in others. We learned to have compassion for others and for ourselves.”

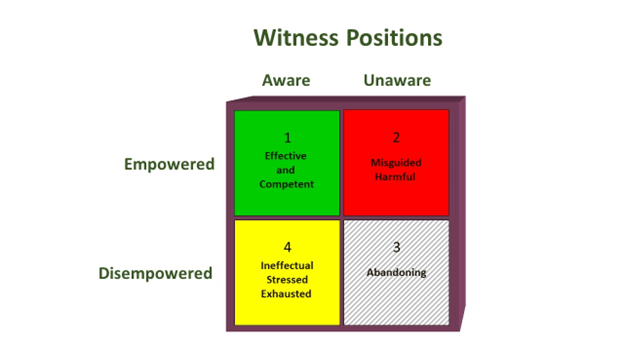

One of the key frameworks we introduce in the learning collaborative for people to understand the impact on others, whether co-workers, family members, or providers, is that of the witness. This is a framework that Dr. Weingarten developed in the early 1990s to account for the impact on people of witnessing violence and violation. Her innovation was to recognize that there is not just one witness position but four. In the context of COVID, many witnesses feel helpless and frustrated, aware of what the person with long COVID is feeling but disempowered in relation to helping them effectively. They don’t know what to do to make the person feel better. Sometimes, because of that helpless feeling, people withdraw from the person with COVID or long COVID. Worse, they may end up forcing or trying to force the person to try solutions that are harmful or prolong their suffering. They are in what we call the “red” square. All of the work in the Witness to Witness Program is to help people find ways of moving into the “green” square where they are aware of what a person is going through and they feel effective in helping them cope.

It is obvious to all of the health care workers who are in our learning collaboratives, and this one was no exception, that the most essential action a witness can take to build resources to support others is to consistently practice self-care. Everyone knows this, but being in the learning collaborative helps providers practice daily the self-care routines that work best for them. Because a community forms, albeit temporarily, they end up feeling accountable to each other to really do self-care. In each of the four sessions, the W2W faculty provide research-based options for self-care that are easy to do in short amounts of time. We share a variety of resources – handouts, comics – that are useful take-aways. All of these resources help providers help themselves and the patients they care for.

Participants in the learning collaborative shared experiences of what we call the “ripple effect.” They told us that they could tell that what they had learned and shared with each other was going to have an impact on how they served their communities, personally and professionally. While these four sessions were in the context of COVID and Long COVID, participants readily noted the application of the ideas we presented to other health issues with which they are engaged. We believe that the sessions strengthened resilience not just for the participants themselves but for the many communities of which they are members. With this learning collaborative, Migrant Clinicians Network enacted its organizational goal of improving the health of underserved communities.

- Log in to post comments