Unsettled: Agricultural Workers and Homelessness in California

[Editor’s Note: Today is Health Care for the Homeless Day, and tomorrow is Agricultural Worker Health Day, two themed days of National Health Center Week. Many of our patients fall into both special populations. Here’s an update on agricultural workers and their unreliable housing options in California’s Central Valley.]

Today, it’s predicted to reach just 90 degrees in Porterville, California, a town outside of Merced in the Central Valley -- it’s the first time a daily high hasn’t gone above 95 degrees in over five weeks. The heat, which seemed stuck at 100 degrees for most of the summer, hasn’t stopped agricultural workers who fill the dusty fields to bring in the summer harvest. Some fields, though, still need more workers. This season, as in recent years, agricultural workers have been in high demand. “[Farms] have had a hard time getting farmworkers, partly because the work is really broken up and seasonal,” noted Sal Sandoval, MD, MPH, a semi-retired and well-loved community doctor who has worked closely with valley agricultural workers and patients without homes for decades. Other factors driving the shortage include the rising age of the average agricultural worker, the slowdown of new agricultural workers coming to the US following the 2008 economic downturn, increased immigration enforcement over the last half decade, a spike of fear due to recent immigration raids, and unavailable and expensive housing. Throughout California, this ongoing multi-year labor shortage has some farmers increasing their workers’ wages while others are retooling their approach to require less labor inputs.

It’s all part of the constantly shifting face of California agriculture, where Central Valley row crops have given way to more profitable vineyards, pastures in the foothills are being converted into orchards with almonds that can tolerate the rocky soil, and coastal cut-flower greenhouses now protect highly profitable marijuana plants. As a result of all these changes, migration patterns have shifted.

Changing Migration

Many agricultural workers who used to return to their home countries are staying put instead -- even if they don’t have secure housing.

“There are people who normally would’ve gone back [to Mexico or Central America] but couldn’t, because it’s so hard to come back again,” related Dr. Sandoval. Both single men and entire families have stayed in recent years, fearing their vulnerability as they cross the border, as many lack documentation (or a portion of the family lacks it) and border controls have become more strict in the last half decade. Fear and anxiety over further tightening of control over the borders and increased ICE presence and broadening of arrests in recent months have immigrants who lack documentation additionally on edge about non-essential migration, both within the US and from the US to their country of origin. Additionally, the traditional “migrant streams” up and down the West Coast and between the Merced region and Texas have slowed, with fewer people making the trek and more workers sticking around full-time and making ends meet during the off-season, likely in part due to the rising age of agricultural workers, as they settle down with their families.

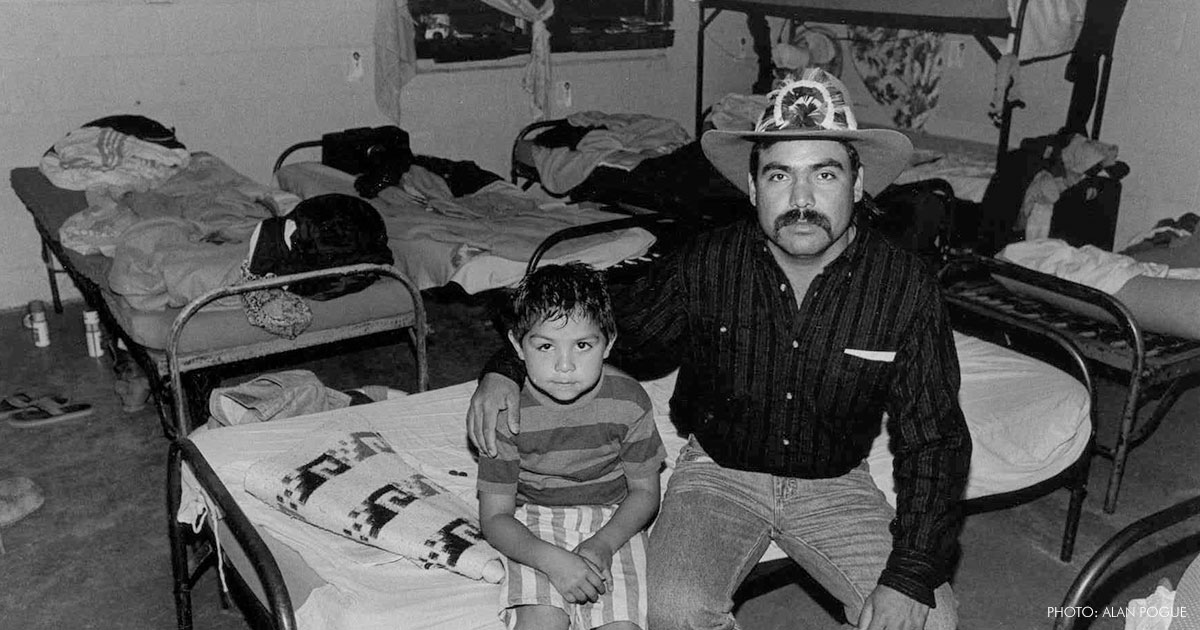

Increased housing competition and higher costs make finding affordable housing difficult. Photo: Alan Pogue.

Housing Needs

The need for year-round housing in an area like Merced is tricky, as the housing market feels strains from other corners as well. Nearby University of California, Merced students and San Francisco Bay Area residents pulled toward the valley by outrageous Bay Area housing prices have increased housing competition and driven up the cost of renting and ownership. Up and down the Central Valley, the story is similar, with housing prices rebounding since the burst of the nationwide housing bubble of 2008 as urban and suburban centers spread eastward onto the valley floor. Like in years past, some agricultural workers will rent together, packing several families in a small apartment. Some agricultural workers in Planada, a largely agricultural worker community outside of Merced, are keeping their less expensive housing and commuting every day to higher-rent locations like Gilroy and Hollister.

Still others are simply unable to find housing that fits their needs, and are taking to the streets. Alaina Boyer, PhD, Director of Research at the National Health Care for the Homeless Council (NHCHC), says that it’s a national problem. NHCHC provides training and technical assistance to health care delivery sites funded by the Health Resources and Services Administration to serve people experiencing homelessness. Currently, there are over 300 health centers nationally with a Health Care for the Homeless (HCH) project with which NHCHC works. Dr. Boyer monitors the trends in homelessness across the country by pulling Uniform Data System information specific to the health centers that have HCH projects.

“There was a big boom in 2015 in the number of agricultural workers who walked through our HCH doors in California,” Dr. Boyer noted. In 2015, 11,844 patients self-identified as agricultural workers. That’s triple the number from 2014, and roughly 16 percent higher than 2013. Dr. Boyer asserts that most of the rise has to do with increased access to health insurance, as many agricultural workers were finally able to seek care. California’s 2016 law to give all children access to health care has resulted in 200,000 children receiving complete coverage under the state’s Medicaid program, Medi-Cal, which may result in an additional increase when 2016’s data is available.

“California is unique,” Dr. Boyer explained. The state’s network of health centers even in very rural locations may help agricultural workers experiencing homelessness access care more easily than in other parts of the country. Also, there’s the sheer number of people living out of doors: California is one of five states that accounted for half of the nation’s homeless population, Dr. Boyer said. But just like in many parts of the country, this population experiences overlapping barriers to access health care. For example, Dr. Boyer sees that California agricultural workers are experiencing an increase in fear around immigration enforcement.

“What we’re hearing is there is some fear around… [the possibility of ICE] coming to our clinics and trying to deport people,” Dr. Boyer said. She has heard of at least one case in which ICE went into a clinic to try to identify people who might be immigrants. For a population battling other barriers to care, the heightened fear and anxiety may be the final straw in keeping agricultural workers from accessing the care they need. “This will be an ongoing challenge for these farmworkers,” she said. Agricultural workers who are experiencing homelessness may be at greater risk of contact with immigration enforcement officers simply due to the fact that they spend more time in public spaces.

“California is unique,” Dr. Boyer explained. The state’s network of health centers even in very rural locations may help agricultural workers experiencing homelessness access care more easily than in other parts of the country.

Strategies for Patients Experiencing Homelessness

Even those who are struggling with homelessness have varying experiences. Some end up sleeping in their cars, while others camp at local parks or in the dried beds of seasonal creeks. Still others may find places to stay, on the floor of a coworker’s apartment for a few weeks, before moving on to another house, attempting not to overstay the welcome. And the health needs of all of these patients vary by season.

“In the winter, you see a lot of respiratory problems. In the summer, more gastrointestinal. With the heat, [food like] mayonnaise gets bacterial overgrowth. Hand washing isn’t very good if [patients] are sleeping outdoors or in the parks,” Dr. Sandoval noted. “We’re not having an issue with obesity among Health Care for the Homeless sites,” Dr. Boyer emphasized. “Food security is a problem, and it adds to the complexity of their health issues.” Close proximity to others and the lack of hygiene double up to help spread disease.

Those with ongoing health needs may find it very challenging to continue treatment. “For diabetics who are on insulin or asthmatics with inhalers, it’s hard with the heat,” which can affect medications. At homeless shelters, refrigeration is available for medication, but for those in very rural areas, shelters aren’t an option. Additionally, without housing, personal items are vulnerable. “Things get stolen all the time -- just another thing we take for granted,” Dr. Sandoval noted. Not only is medication stolen, and not easily replaced, but their identification cards and cell phones can also be taken, leaving them unable to be reached, or to check in at the health center.

The Future of Mobile Health: Flexibility

For Central Valley agricultural workers, the future remains cloudy. It’s unclear whether increased farm wages in the region have been swallowed up by the rising cost of living, whether rising wages will last, or what the political situation will spell for those who lack documentation, but such changing forces demonstrate the complexity of agricultural workers’ situations year by year. This makes it difficult to predict how these overlapping social factors will affect agricultural worker health. For clinicians serving mobile patients like Dr. Sandoval, the key is flexibility and patience -- and a willingness to shift as the seasons progress. “Right now, there’s work, so I think people have the best likelihood of not being out in the streets,” Dr. Sandoval noted. “Many people [have] unsettled immigration situations,” which means caring for agricultural workers who have unstable housing just got even more complex.

Resources

The National Health Care for the Homeless Council’s website is full of tools and resources for clinical practice. We recommend their Adapted Clinical Guidelines, and their fact sheets, which include relevant topics like their Prevention & Response to Infectious Diseases Within the Homeless Population and the HCH and HIV fact sheet.

Like what you see? Amplify our collective voice with a contribution.

Got some good news to share? Send it to us via email, on Facebook, or on Twitter.

Return to the main blog page or sign up for blog updates here.

- Log in to post comments