Tick Time! A Basic Primer on Ticks for Clinicians Serving Outdoor Workers

Ticks, like I. scapularis (black-legged tick) on the East Coast, have been present in North America for at least 500,000 years, arising as a species in what is now the southeast United States, and expanding north between glaciation periods. The number of ticks decreased significantly after colonization of the Americas with the decimation of white-tailed deer populations, and extensive deforestation during the industrial age. As many states made efforts to re-forest, and re-populate the white-tailed deer population, tick populations increased and expanded again starting in the southeastern U.S. and expanding north and west. In the last 20 years, the number of counties with established populations of I. scapularis has doubled. Many species of ticks live across the country, like I. pacificus (Western black-legged tick) on the West Coast, D. variabilis (American dog tick) east of the Rockies, A. americanum (lone star tick) in the Northeast, South, and Midwest, and more.

With ticks come a wide variety of diseases that are difficult to diagnose and properly treat. Testing algorithms are complicated, and few clinicians are familiar with them due to lack of experience and training. Additionally, few states in the central US report data on ticks either due to lack of sampling and/or reporting the presence of ticks, leading many clinicians in those states to believe that tick-borne disease in not present.1 To see maps for various types of ticks and illnesses ticks carry in the United States, click here to visit the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Tickborne Pathogen Surveillance page.

Throughout the US, communities are experiencing warmer weather earlier in the spring, and later into autumn. Changes in weather have created a longer tick season than ever in recent history, with an earlier appearance of tick nymphs. Because tick nymphs are very small and hard to spot, they bring an increased risk for bites and exposure to disease because people do not know they are on their body.

People that live in, visit, or work in areas that are known to have a high tick population can take measures to prevent exposure to ticks when they visit areas known to have a large tick population. Clinicians working with outdoor workers like migratory and seasonal agricultural workers are encouraged to alert their MSAW patients about ticks, as outdoor workers may be at higher risk, particularly when working along the edges of forests and in high grasses.

The CDC recommends the following, which clinicians can communicate to their patients:

- Know where to expect ticks both geographically (varies by type of tick – visit CDC to find maps), and the environments they prefer (wooded, brushy, grassy landscapes, as well as on animals, including livestock and pets).

- Treat clothing and gear that you will wear while visiting/working in such areas with products that have 0.5% permethrin or buy clothing that already is treated with permethrin.

- Avoid ticks by avoiding wooded or grassy areas, or staying in the middle of paths when walking in those areas to avoid brushing against plants where ticks are questing (the term for when ticks are feeling for changes in the environment and attempting to get on a potential host).

- Use insect repellent that contains DEET, picaridin, IR3535, oil of lemon eucalyptus (OLE), para-menthane-diol (PMD), or 2-undecanone according to package instructions. (Do not use products with OLE or PMD on children under three years old.)

If you have visited or work in an area that may have ticks, even if you have done all the above, it remains important to also do the following:

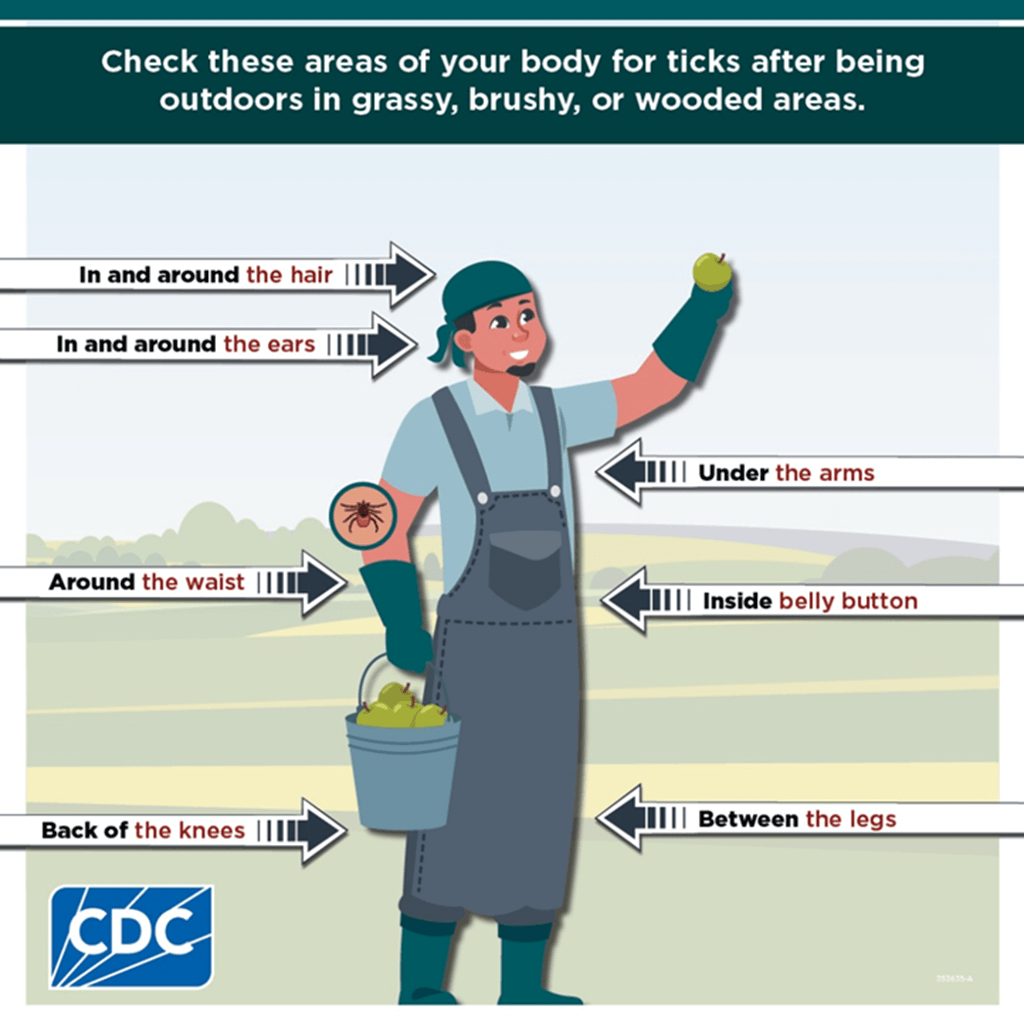

- Inspect your clothing and body for ticks. Because tick nymphs are very small and hard to spot, be extra vigilant in your search. Each region has a different season for nymphs, and those seasons may be changing. Mild-weather areas like California may see nymphs in the winter; other areas may see them in early spring. Still other areas, like high-elevation mountains, may not see nymphs until later in the spring.

- Examine pets and gear.

- Shower as soon as possible after returning indoors, changing clothes when you return home. Many agricultural workers live temporarily or year-round in rural areas where backyards and environs have a higher risk of ticks. Wash clothes in hot water and a hot dryer temperature before wearing again. If you cannot wash clothes right away, store in a sealed plastic bag to prevent ticks from spreading indoors.

Here are some steps they can take to minimize ticks in their yards, especially if they live in areas known to have large tick populations:

- Clear brush, tall grass, and leaf litter around your home or edge of lawns.

- Mow the lawn often.

- If your yard backs up to wooded areas, put a three-foot-wide barrier of wood chips or gravel between the lawn and the wooded area to decrease tick migration.

- Keep patios, decks, and play areas away from the edge of a wooded area.

- Stack wood neatly and in a dry area to minimize rodent infestation (that may carry ticks).

Tick Removal Instructions

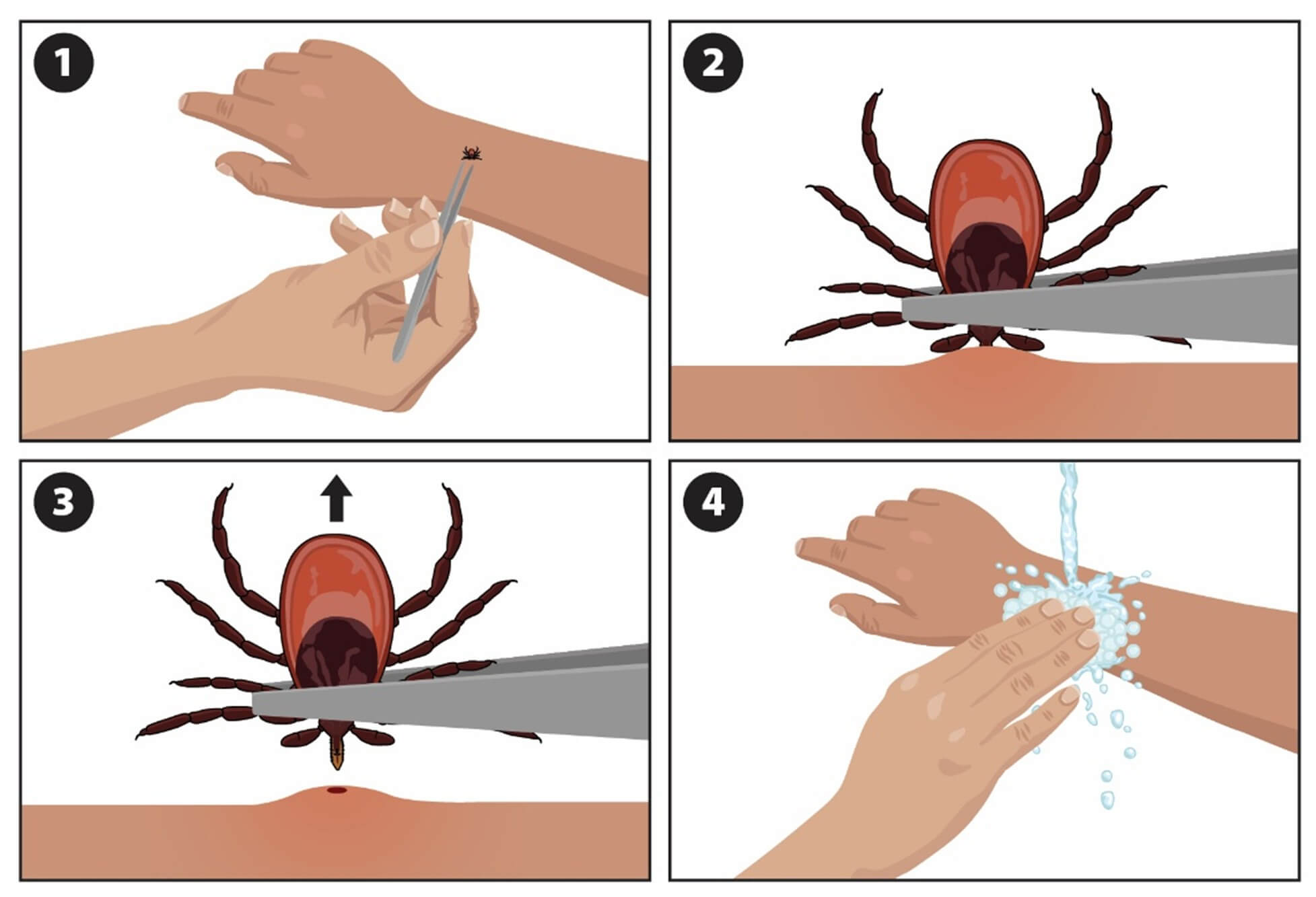

Remind your patients: If you find a tick on you, or in your skin, remove it immediately. Don’t wait to see a health care provider or other person. The longer it is attached, the more time it can potentially transmit disease. Here is the best way to remove a tick from your skin, according to the CDC.

- Use fine tip tweezers if you have them; if you do not, regular tweezers or even your fingers will do. Pinch the tick as close to the surface of your skin as possible. Do not pinch the body.

- Pull the tick out with slow, even pressure. Do not twist or pull too quickly, which can cause the mouth parts to break off and remain in your skin. If this happens, you can try to pull them out with the tweezers, but if you cannot get at them, leave them. Your skin will eventually push the mouth parts out as it heals.

- Dispose of the tick by flushing it, putting it in alcohol, or putting it in a plastic bag sealed with tape (if they wish to preserve it for testing).

- After you have removed the tick, wash the bite area and your hands with soap and water, hand sanitizer, or rubbing alcohol.

- Note: If you found one tick, there may be more. Do a very careful search of the rest of your body.

- Finally, if you develop a rash or fever a few days or weeks later, see a healthcare provider right away and let them know about the tick. Some people keep the tick in a sealed container for a few weeks so it can be identified, along with the types of illness that type of tick may carry, if they were to become ill.

Don’t let ticks stop you from enjoying the outdoors! Ticks have been around a long time, and are likely to continue to expand their territory rather than go away. Being prepared is your best bet to prevent them or handle them if you happen to get one on you!

Resources:

- Local Lyme disease map: Clinicians can check the incidence of Lyme disease in their county, and changes over time. Visit this page from Johns Hopkins and scroll down to “What’s going on where I live?” Enter your county’s name in the Search bar. For a national map and data, use their maps of US, Canada, and Global incidence of Lyme disease.

- La enfermedad de Lyme: Access basic information, including symptoms and prevention, in Spanish on the Mayo Clinic site, or watch this video in Spanish from CDC: Lo que necesita saber sobre la enfermedad de Lyme.

- Low-literacy and multilingual flyers/info cards: Pennsylvania has resources on “Fight the Bite”, “Permethrin and Repellant,” and “Tick Check and Removal” with info in English, Spanish, and Haitian Creole.

- Climate Change and Tick-Borne Disease Risk: Read more about longer tick seasons and larger ranges in this short summary of the data and the Cary Institute’s responses.

1 CDC. Selected Tickborne-Disease Surveillance, 2019-2022. https://www.cdc.gov/ticks/data-research/facts-stats/geographic-distribution-of-tickborne-disease-cases.html. Accessed: 7/2/25.

- Log in to post comments