Birth Defects: Anencephaly and Health Justice in Washington State

Editor’s Note: Jennie McLaurin, MD, MPH is MCN’s Specialist in Child & Migrant Health and Bioethics. She is a member of the Washington State Department of Health Anencephaly Advisory Committee. The committee works alongside the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to better understand the increased rate of anencephaly recently observed in Washington State. Dr. McLaurin will present on anencephaly at the 2015 Western Migrant Stream Forum in San Diego, California. Her talk, entitled “Birth Defects in Our Babies: Washington's Outbreak and the Outreach Answer,” is scheduled for Wednesday, February 25, 10:30am-12:00pm.

January is National Birth Defect Prevention month. Frankly, there are so many causes attached to months, that sometimes the designations seem meaningless. As for birth defects, most of us imagine a child in leg braces on a poster, and we aren’t sure we have recently known an affected family. Further, if we aren’t going to be pregnant, it isn’t a headline-grabbing issue.

The news in Washington State, though, is front page for all who are concerned about health justice. Rates of a fatal rare birth defect, anencephaly, have quadrupled in areas where farmworkers and their families reside. Further, Hispanic women are already at higher risk for this problem than women of other ethnicities.

Birth defects can be as simple as a tiny extra toe, to as complicated as conjoined twins. Increasingly, expectant parents use technology to examine their fetus long before the due date. Sometimes, these tests allow doctors to plan treatments during or just after the pregnancy, to correct the problem. But for some serious and deadly birth defects, it is always too late to heal the baby by the time it is found. That is the case with anencephaly.

Anencephaly, which literally means “without a head,” is the congenital absence of most of the brain, along with some of the skull and scalp, and with an open spinal cord. It is in the category of neural tube defects, with spina bifida being a milder version of the same process. Anencephaly is the rarest of the neural tube defects. The neural tube, which forms the spinal cord and brain, forms and folds very early in pregnancy, typically between 23 to 26 days of gestation. Thus, many women do not even realize they are pregnant when the presence or absence of this defect is determined.

Anencephaly, which literally means “without a head,” is the congenital absence of most of the brain, along with some of the skull and scalp, and with an open spinal cord. It is in the category of neural tube defects, with spina bifida being a milder version of the same process. Anencephaly is the rarest of the neural tube defects. The neural tube, which forms the spinal cord and brain, forms and folds very early in pregnancy, typically between 23 to 26 days of gestation. Thus, many women do not even realize they are pregnant when the presence or absence of this defect is determined.

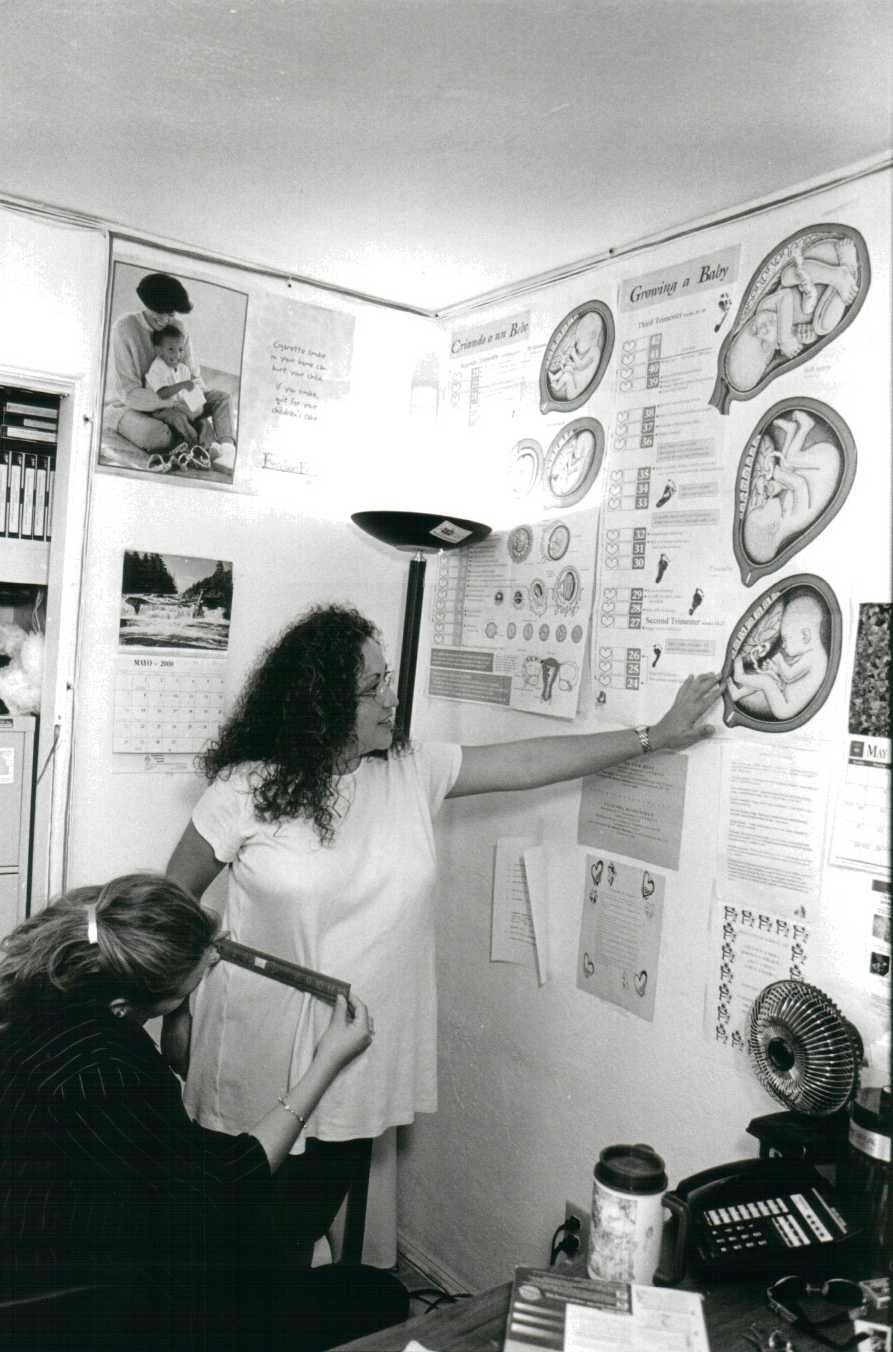

Fortunately, recent science shows that nutrition can be a strong protective factor against neural tube defects. Diets rich in folate, the vitamin found in leafy green vegetables, and also in citrus, beans and nuts, protects neural tube formation. For the past 25 years, folate has been routinely recommended as a prenatal vitamin and it has been added to commercially prepared breads in the US. However, since neural tube closure occurs so early in pregnancy, all women who may become pregnant are encouraged to ensure they are eating foods rich in folate. Since folate has been a regular component of pre-conceptual and prenatal care, rates of anencephaly have fallen, with expected rates now of only two babies per 10,000 births.

That progress seems to be disappearing in parts of Washington State. Five years ago, clinicians noticed that several babies were born with anencephaly in their rural Yakima area, in the agriculturally rich valley located in central Washington State. Clusters of cases are often just coincidental, but when more babies were also noted to be affected in two other Washington counties, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) was contacted and they launched an investigation. Rates in the three counties were over eight per 10,000, which is four times the expected number. Analysis of several years’ births showed persistently high rates, with 2014 showing the highest rate ever, perhaps as much as 12 to 14 per 10,000.

Until this year, the rates have only been studied retrospectively. The state does not have a birth defect registry that includes neural tube defects, and no systematic reporting for these birth defects occurs. Thus, the rates are known only because a trend seemed evident and hospital chart reviews revealed the diagnosis. The rate also does not include any prenatally diagnosed cases that were medically aborted.

So far, the cause of the high rates of anencephaly is not known. Typical risk factors include: Hispanic ethnicity; exposure to neurotoxins such as pesticides; use of certain medications; obesity; family history; and folate-deficient diets. In this outbreak, there is not a difference in the socioeconomic, age or ethnic status of women with affected babies compared to those without. Farm work history is only known by hospital chart report, but occupational data does not yet reveal a significance. Pesticide exposure is highly suspect, but methods in measurement thus far do not show a relationship. While the affected region is distinctly agricultural, rates of the defect were initially similar for mothers living on farms and away from farms. Recently, zip codes of affected women were further analyzed, and it appears that rates are indeed higher for women living on or next to farmland. Diets have been lower in folate in the affected women, but women in the unaffected group are also less likely to have folate rich diets.

Corn flour used in tortillas is not folate-enriched. This issue has been presented to the Food and Drug Administration, but there is no current plan to address prevention through corn flour enrichment. Pesticide exposure levels have not been measured by cholinesterase testing, historical recall, or detailed work histories. Water sources are currently being examined for fertilizer residues and other toxins. Large-scale public messaging campaigns about prevention of neural tube defects is just starting, and is largely absent in low-literacy Spanish language format.

Five years have passed since concerns over the rise of anencephaly were voiced. The causes are clearly multifactorial, but folate is known to be of tremendous protective benefit. Pesticides are known to be neurotoxic. These two things are clear, and prevention efforts still lag behind our knowledge of what works. Most of the families in Washington who lost their infants with anencephaly were not aware of the disease or ways to prevent it.

Health justice leaves us dissatisfied with health disparities affecting underserved populations. The women most at risk in these cases live in rural, farm-dense communities with well water, large Hispanic communities, regular aerial spraying of pesticides, and inadequate preventive health education. Regulations around food, water, and occupation fail to protect them from a number of disease threats, including anencephaly. Cause is difficult to determine, but risk is at least partially understood. We must make every effort to campaign for the well-being of these women and their children and provide access to nutrition, clean water and air, and education on how their occupation or home environment may impact their health. Careful monitoring of neural tube incidence should be championed in order to fully understand the scale of the problem and further study the factors that are resulting in such devastating birth defects.

Learn More:

Washington Department of Health’s Anencephaly Investigation

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Key Findings

- Log in to post comments