Then and Now: COVID Exacerbated Health Inequities, But Also Built Opportunities for Ongoing, Trusted, Culturally Contextual Public Health Responses

[Editor’s Note: We’re entering Year Four of COVID. At a recent webinar hosted by the Center for Disaster Philanthropy, Migrant Clinicians Network’s Amy K. Liebman, MPA, Chief Programs Officer of Workers, Environment, and Climate gave a summary of how COVID has greatly impacted communities of color – and how MCN stepped in to assist, utilizing new streams of funding. Here, we summarize her presentation. Read more about the webinar, COVID-19 Year Four: Implications for Philanthropy, and access the link to watch the full webinar, at the Giving Compass blog.]

Migrant Clinicians Network is a national nonprofit dedicated to health justice. We have two primary audiences: the frontline clinicians who serve immigrants, and the immigrant and migrant communities themselves. When we look back at the beginning of the pandemic, it is a story of not only sickness and death, but one of moral injury, and failure and neglect of government.

The pandemic began rather indiscriminately. COVID-19 affected all people, regardless of race, ethnicity, or economic status. That quickly changed as quarantine policies took hold, and schools and workplaces closed or shifted online. Workers deemed “essential” had few options; those on the frontlines of health care and food production were expected to work -- and, in many cases, these workers had no other economic option.

Our health care providers were expected to care for the ill with limited PPE and very few policies to protect them such as a basic airborne pathogen standard. For a good deal of the pandemic, health care workers were three times more likely be infected with COVID-19 compared to the general public.

In our immigrant, migrant, and BIPOC communities, the health inequities were staggering. For a large segment of the pandemic, the case and death rates in our Latinx and Black communities were more than two to three times that our of our white communities -- and that is largely due to work:

- 69% of all immigrants in the labor force are essential workers;

- 74% of unauthorized immigrants are essential workers; and

- Almost half of all DACA-eligible immigrants are essential workers.

For those of us living in communities where immigrants fuel our food production, the impact of COVID was striking. I live in Salisbury, on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. Ten chicken processing plants are within a 75-mile radius of my home. Haitian, Guatemalan, and Mexican immigrants, along with members of our African-American community, work in these plants. These workers were unprotected, with limited or no sick leave policies, limited access to PPE, and poorly ventilated workspaces. They quickly became sick and many died -- and then their children and family members started getting sick.

The blame came swiftly: It was their culture, the way they lived, etc. There was little acknowledgement – in fact, there was some outright refusal -- regarding the work-relatedness of this virus and the conducive conditions in the workplace.

The blame coincided with chaos, inept federal response, lack of trusted information, and insufficient and, at times, inaccurate emerging understanding of COVID. I remember so clearly working from MCN’s Puerto Rican office the second week of March 2020, just before our quarantine policies took hold. I decided to return home early, leaving Puerto Rico on March 13. At the airport I recall seeing two women wearing masks. And I thought to myself, why are they wearing masks? The CDC says it is not airborne. And I proceed to my seat which I thoroughly sanitized, flew maskless, and went home to my family.

Technical Assistance in the Absence of Funding

A week after that flight, without funding and appropriate staffing, Migrant Clinicians Network sprinted into response, with no idea that we were going to be running a marathon. Through all kinds of virtual venues, we translated the rapidly changing science and guidelines, brought panels of clinicians together to share what they were doing with their migrant and immigrant patients and how they were protecting themselves. And we advocated to protect both clinicians and workers.

But perhaps most importantly, we listened to the needs and challenges and kept responding. We quickly realized this was also a pandemic of mis- and disinformation. We responded with resources and training. We provided psychosocial support to frontline clinicians suffering from moral injury and the trauma they were witnessing. By May, we presented to hundreds of clinicians one of the first national webinars underscoring the airborne aspect of the pandemic.

We stood up when the government told us to stand down. One of our federal funders, that supports our worker training program, specifically told us we could not use these funds to train workers about COVID-19. We carried out our deliverables and then doubled our work efforts to ensure workers and community health workers (CHWs) were getting the information they needed in a way that they understood – even when we didn’t have the funding.

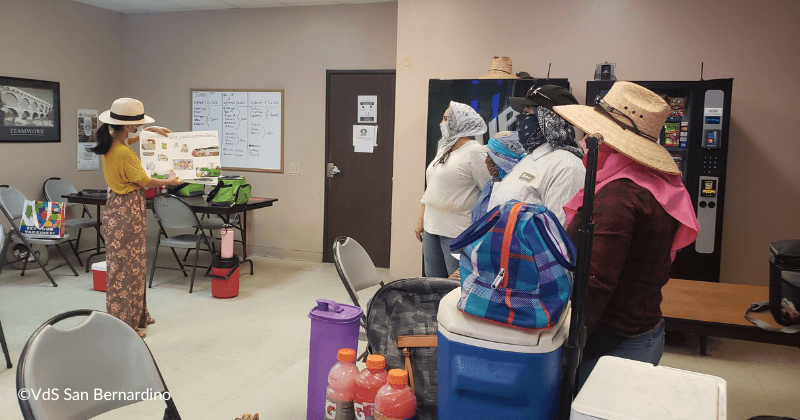

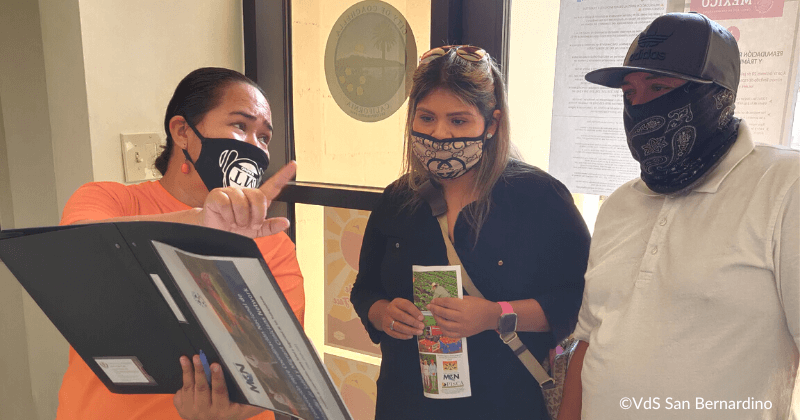

By fall of 2020, substantial funding finally came in the door, allowing us to hire staff. We partnered with community groups across the country to develop culturally contextual resources with messaging on how to stay safe. This merged into our “Vaccination Is…” campaign, with nearly 300 resources in multiple languages that community groups can easily adapt with photos of local trusted messengers, as well as logos and local phone numbers. And we did an extraordinary amount of work to try to help health departments engage in an equitable and bidirectional relationships with disenfranchised community members.

One of most intensive efforts involved a partnership with Alianza Nacional de Campesinas, a network of more than 20 community organizations across the country. They were awarded $8.5 million for vaccine outreach to spend in six months. We provided intensive technical assistance, facilitating weekly learning collaboratives with clinical and policy updates, resource sharing, and strategies for reaching communities. We also addressed challenges, from misinformation to racism. One of our community partners in Kansas was surrounded by trucks waving Confederate flags as the CHWs tried to carry out a vaccine clinic for their largely Black community members. I am happy to report that they were incredibly successful, despite the intimidation. And by the end of 2021 we saw drastic changes in disparities. In some communities, we saw vaccination uptake for Latinxs exceeding that of non-Latinxs. We are continuing to disseminate resources and best practices.

Looking Ahead

The hyper-local aspect of the public health response was critical and the role of CHWs was essential. Continuing to nurture and train our CHWs outside of the crisis will be an important area of funding focus for health equity and justice.

We also provided a good deal of financial technical assistance. An $8.5 million grant is always welcome but in six months and with very limited prior government funding experience, this was not necessarily an easy task for our partner. But they did it, and their work was amazing. We saw the needle move in terms of the disparities around COVID -19. However, it ended with some significant community layoffs. Some of the future funding may simply involve philanthropic trust and support for some of these organizations with long-term general operating costs to carry out health-related community work – because building trust within a vulnerable community takes time and dedication and cannot be called up when there’s a new emergency. It is a long-term game requiring assured funding.

Public health and our health care system have taken enormous blows. Trust in health authorities was eroded across the entire COVID timeline, and as COVID-specific funding winds down there is much work to be done to support and fund CHW programs and other outreach efforts to build communication conduits between health authorities and underserved communities. These same efforts are successful at building health equity and justice. We need to ensure that the working conditions for all clinicians improve, including systemic changes with real attention to supporting their psychosocial well-being. For our larger worker community, we need firm recognition that workplace policies are public health policies, with commitments to strong yet basic workplace policies like paid sick leave. – and we need to continue to advocate for universal health care.

In the last four years, despite these many challenges and missteps, we have made important strides toward health justice: universal access to vaccines and treatments during the pandemic have been critical. And we can’t afford to go backwards. As we move into a new phase of the pandemic, the lessons we’ve learned about the importance and effectiveness of culturally relevant and trusted outreach for underserved communities cannot be abandoned.

- Log in to post comments