Worker Safety is Safety for All of Us

Photo by Earl Dotter

By Amy K. Liebman, Director of Environmental and Occupational Health, Migrant Clinicians Network

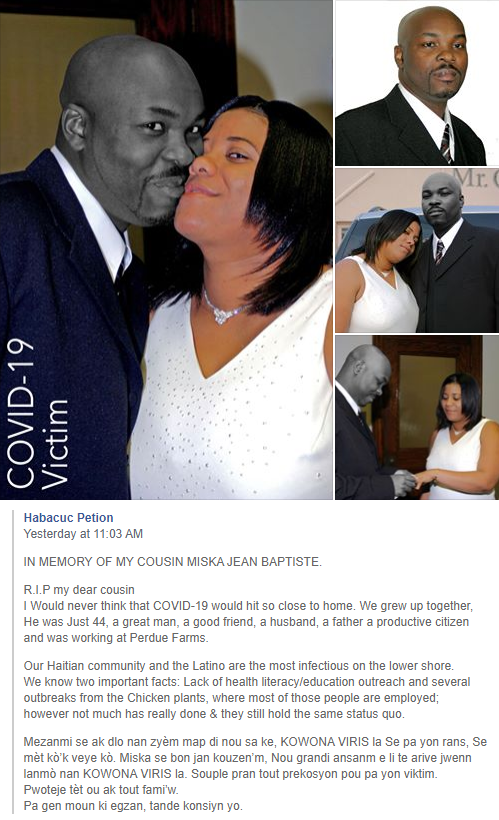

“There are mountains beyond mountains. The struggle continues.” Citing the Haitian proverb, my colleague (and former MCN Board Member) Wilson Augustave wrote these words in response to my Facebook post where I shared the grief of my friend Habacuc Petion who had just lost his cousin, Miska Jean Baptiste, to COVID-19. His cousin, who was also a husband, father, and friend to many, worked in a chicken plant in my hometown of Salisbury, Maryland.

COVID-19 has shown no mercy to the meat packing industry. “Hot spots” of COVID-19 across the country have devasted workers, with hundreds sick and many dying. Sioux Falls, South Dakota, home to Smithfield Foods and one of the largest pork processing plants in the country, has the biggest cluster of cases in the US, forcing Smithfield to shut its doors. Lousia County Iowa, home to Tyson processing plants, now has a higher coronavirus rate than New York State. Four workers from a Tyson chicken plant in Georgia have died. The coronavirus knows no boundaries, and the families and communities where these workers live suffer too.

With each report, my fear for my community on the Eastern Shore of Maryland has grown. We are in the heart of chicken country here on the Delmarva Peninsula and chicken fuels our local economy. In 2019 alone, we processed 4.3 billion pounds of chicken with a workforce of over 20,000 employees. The cornerstone of this industry are workers from Haiti, Guatemala, and Mexico as well as many African Americans. It’s a grueling job noted for is high rates of injury. Almost all confirmed coronavirus cases at our local hospitals have some connection with the chicken plants. In fact, screening patients for COVID-19 now includes questions about work and their connection to poultry processing. One company admitted that the coronavirus outbreak has hit its staffing levels so hard that it cannot keep up with production, slowing production by fifty percent. Mountaire Farms and Perdue Foods have acknowledged confirmed cases in their plants, but are not sharing the number of sick workers associated with their plants. Our COVID-19 numbers in Wicomico County and neighboring Sussex County, Delaware continue to exponentially increase. We’ve yet to hit our peak in this largely rural area and hospitals are filling up.

Habacuc’s post saddened me and I called him to see how he was doing and what I could do to help. He said it’s been a rough couple of weeks. He, too, was sick with what he suspected was coronavirus. He had good reason to believe he had COVID-19; his mother, who he took to the hospital 13 days ago, tested positive for COVID-19. Knowing he was exposed, he self-quarantined and within in a few days had a high fever and achy body. He is grateful to be on the mend but is so worried about our Haitian and Latino communities. They need more education and outreach to understand how to prevent this disease and not enough is being done in the plants, he said. They work so close together. There’s confusion among workers about their ability to call in sick. He said many think they need a doctor’s note as before the pandemic, any absence due to illness required a doctor's note, and it's unclear to workers whether that still holds true. Others feel obligated to work, he said. Workers are hearing the news about “essential” workers and the faltering of our food supply under pressure from the virus. They also need to work to survive. But they are scared, he said.

Photo by Earl Dotter

Perdue Foods, one of the primary chicken processers here in the region, has said it’s making changes. Workers are now spaced farther apart, are given personal protective gear, and have their temperature checked. The rapid speed of the production line has been slowed to allow protective barriers to be placed between workers. These are all steps in the right direction, but it may be too little, too late. Temperature checks miss an estimated 25 percent of people with COVID-19, as they are asymptomatic. The spread has already begun.

Others are fueling xenophobia. Smithfield and the South Dakota governor, who has refused to issue a state-wide stay at home order, are now blaming the immigrants themselves for the spread. This is despite the company’s dangerous labor practices that led to this massive outbreak. I am scared for what comes next.

My day ended with a call from a friend, sharing the heartbreaking news that one of the beloved players from my son’s old soccer team was being hospitalized with COVID-19. He is 20 years old. His mom works at the local chicken plant. We are a small community and our lives are intertwined from the soccer pitch to the classroom to our work.

It’s our “essential workers” -- our health care providers, grocery store clerks, first responders, food producers and farmworkers -- who are on the frontlines of this pandemic. They are also our neighbors, our friends, our teammates, and our co-workers. Our response to this virus has been slow and uncoordinated, and in many cases, has blatantly ignored the science with deadly consequences. Testing and contact tracing – basic public health practices used to fight pandemics -- are so limited that we have no idea the extent of this pandemic in the US. Doctors and nurses are desperate for personal protective equipment. The Centers for Disease Control has issued guidelines to help employers and businesses respond to COVID-19. But the agency responsible for worker safety, OSHA, refuses to make these guidelines mandatory for workplaces, nor has OSHA adopted other new rules to help ensure worker safety. In fact, OSHA has been largely missing in action. Refusing to issue any emergency standards and reneging on its enforcement duties, OSHA has essentially told workers that they are on their own.

In spite of these deadly missteps, one thing is clear: worker safety is public health. And if we are not helping our workers stay safe, we all are at risk.

Like what you see? Amplify our collective voice with a contribution.

Got some good news to share? Contact us on our social media pages above.

Return to the main blog page or sign up for blog updates here.

- Log in to post comments