Why is the implementation of comprehensive occupational health programs for school personnel essential for a safe reopening of schools? A summary of our most recent training program in Puerto Rico

By: Marysel Pagán-Santana, DrPH, Puerto Rico Senior Program Manager

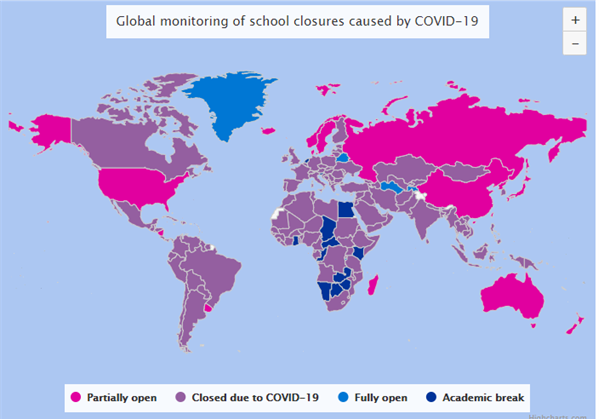

One of the most repeated topics of public discussion in Puerto Rico and around the world is the opening of educational institutions amid the COVID-19 pandemic. According to UNESCO, this public health emergency has caused the closure of schools nationwide in more than 160 countries, affecting more than 1 billion students [Figure 1]. This organization points out the consequences of school closures, ranging from the physical safety and health of the student body, the economic costs that the closure causes in families in the search for childcare, to the pressure on educational systems to remain open and the stress this could cause on school personnel. In a broader context, health and education cannot be separated from one another both in the risk of contagion in places and in the role of education as a social determinant of health.

Figure 1. Graphic generated by UNESCO for monitoring school closures due to COVID-19. This visualization shows the global state for the month of May 2020, where the highest number of students and schools affected was reached.

According to the CDC, the social determinants of health are those conditions in the environment where people are born, live, are educated, work, recreate, and develop, that affect health and quality of life. Some of these determinants are employment, food security, neighborhood security, housing, access to health services, and education. The latter, according to recent reports and studies, can impact health and quality of life in the long term. A complete and quality education is a factor that modifies the ability to find employment and generate income. This in turn can influence where a person lives and what access to health services they have on hand. The Nation’s Health, a periodical publication from the American Public Health Association (APHA), argues that “education is not just what you learn in a classroom; but it also opens the door to future well-being.” The implications that the closure of schools has on the development, and physical and emotional health, of children creates a dilemma of what is riskier or what is the best way to guarantee both health and education.

Several organizations have been given the task of studying the risk of transmission of COVID-19 in school environments and have collaborated in the development of guidelines that support sensible decision-making. The World Health Organization (WHO) has a guide which provides a checklist for making informed decisions and implementing controls in schools. Additionally, WHO, in partnership with other organizations, has collaborated in the continuous surveillance of schools to understand the dynamics of contagion. This surveillance is needed to improve guidance to schools and advise countries regarding reopening. It is worth highlighting a recent WHO report that presents several findings regarding the transmission of the virus in schools globally, including the distribution and dynamics of cases among students. It also assesses whether the opening of schools causes an increase in cases at the community level. Some key points of the report include: 1) the closure of schools did not cause a greater reduction in cases compared to other policies such as the use of masks and physical distancing in public places; 2) most outbreaks in schools likely originated from adults or school personnel and not from students; 3) most of the outbreaks were reported in secondary/high schools; and 4) there is a strong association between the number of outbreaks and community contagion, where more outbreaks were observed in communities that had high numbers of infected inhabitants. This type of report, in conjunction with other studies and surveillance systems, indicates that school reopening can be carried out safely by following specific indicators of contagion at the community level and implementing protocols and policies that promote occupational health of the personnel who work in these environments.

The CDC has published indicators that guide the school community to carry out a safe reopening of their facilities. There are three core indicators: the first two measure the amount of cases in a community and the third is a self-assessment of the school capability to implement key mitigation strategies. The mitigation strategies focus on facial coverage, hygiene, and distancing. The use of these indicators provides a route for government agencies to make decisions regarding opening, but also for the school community to have an idea of when it might be safe to return to campus. Even though most of the indicators (core and secondary) are tied to the community dynamics of the place where the school is located, the protocols and their implementation fall heavily on the school administrators. Having the resources and personnel required for the effective implementation of protocols and programs for the prevention of contagion can be a challenge for those schools with limited resources or that have infrastructure already in disrepair prior to COVID-19. In Puerto Rico, many schools are challenged by the process of developing and implementing protocols while still recovering from other disasters or emergencies.

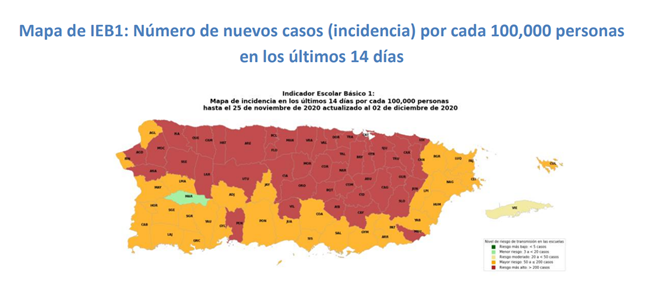

Puerto Rico: Overlapping Disasters Make School Reopening Difficult, and More Critical

Puerto Rico has experienced numerous naturals disasters, largely as a direct consequence of the climate crisis. Weather-related emergencies such as the hurricanes of 2017 and the drought of 2020, in combination with significant earthquakes in 2019 and 2020 and the public health emergency of the COVID-19 pandemic, add additional pressure to the education system and reduce its ability to respond quickly to the needs of the school community. Despite these difficulties, a possible in-person return is being evaluated for early 2021. This is being considered due to the difficulty of implementing distance education, in part because of the fragility and insufficiency of the technological and electrical energy infrastructure; the socioeconomic profile of the students, where the majority are below the poverty level; and the educational disparity that increases for those students with limited resources. Following the guidelines established by the CDC, the Puerto Rico Department of Health has monitored and presented on the risk of transmission in schools. In their reports, almost all schools are in areas of greater transmission or higher risk of transmission. Although Puerto Rico is not in the best position to return to school in person, it is appropriate to plan and develop protocol for implementation phases. Such advanced preparation ensures that, once communities reach low contagion levels, schools can quickly comply with all the indicators to be able to reopen while preventing COVID-19 spread.

Figure 2. Level of risk of transmission in schools in Puerto Rico as reported by the Department of Health.

School Personnel Training: MCN’s New Project in Puerto Rico

An integral part of an efficient and sustainable health and safety protocol is the training of the personnel who will be implementing and ensuring compliance. Training the school sector not only fosters a safe work environment, but also helps the sector to identify limitations and provide solutions to it while empowering staff to manage and reduce the risk of contagion in individual activities. School personnel are an important group of essential workers who need tools to enable them to return to work safely. Advance training allows schools to addressing the concerns in such a way that lessen work stress brought on by a lack of knowledge of effective and adequate mechanisms to protect oneself. Within the public discussion, some of the questions or concerns expressed by teachers or other participants in the educational system included risk analysis strategies, knowledge of indicators to know when it was safe to return, and alternatives to avoid being infected in the workplace. Considering the concerns of the community in general, Migrant Clinicians Network (MCN) proposed a program to conduct capacity building interventions with the school staff with the ultimate objective of helping them share the information to the broader school community including parents, students, and other members of the community.

During the past six months, MCN has carried out two virtual series of four workshops each, specifically for school staff in Puerto Rico, reaching a total of 284 participants, through MCN’s new partnership with the Rutgers University Center for Public Health Workforce Development, as part of a grant from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS). The first series was directed at teachers and personnel of the public educational system, with representation from all the educational regions in Puerto Rico. The second series was adapted to focus on the private sector serving students with functional diversity. In this case, the school staff included all professionals in charge of providing speech and occupational therapy, in addition to teachers and administrative staff. For four consecutive weeks, the participants attended workshops where they were introduced to clinical and epidemiological aspects of COVID-19, the regulatory framework related to occupational exposure, risk assessment and controls to mitigate risk, and the best practices in school settings. These interventions gave participants a clear overview of what to expect in decision-making at government, administrative, and community levels, as well as individual strategies for the needs of different educational activities. Part of the discussion also included a reflection of the possibilities for adapting the academic curriculum considering the current public health emergency. The exchange of information and discussion developed in these educational activities have promoted the identification of new opportunities for growth and training in the school settings to promote safe and healthy work environments. Similarly, we continue our collaboration with this essential sector in other areas such as safe water management and natural disasters as part of a grant from the Environmental Protection Agency. (Stay tuned for future updates!) We will continue our worker health and safety training program during public health emergencies, serving other labor sectors and collaborating with Hospital General Castañer in Lares, Puerto Rico. The need for worker training is great and it is essential to be able to cope with and overcome the emergencies concurrently confronting Puerto Rico and the rest of the world.

- CDC (2020) Indicadores de ayuda dinámica para escuelas.

https://espanol.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/schools-childcare/indicators.html

- Departamento de Salud de Puerto Rico (2020) Informes semanales sobre la dinámica del COVID-19 para la toma de decisiones en las comunidades escolares en Puerto Rico.

http://www.salud.gov.pr/Pages/Comunidad_Informes_COVID-19.aspx - Departamento de Salud de Puerto Rico (2020) Informe semanal sobre la dinámica del COVID-19 para la toma de decisiones en las comunidades escolares en Puerto Rico (Informe de diciembre).

http://www.salud.gov.pr/Documents/Informe%20semanal%20din%c3%a1mica%20del%20COVID%20-%202%20dic%202020.pdf.pdf

- Health, T. L. P. (2020). Education: a neglected social determinant of health. The Lancet. Public Health, 5(7), e361. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanpub/article/PIIS2468-2667(20)30144-4/fulltext

- McGill, N. (2016). Education attainment linked to health throughout lifespan: exploring social determinants of health.

https://www.thenationshealth.org/content/46/6/1.3

- Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (2020) Social Determinants of Health

https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/social-determinants-health

- Shankar, J., Ip, E., Khalema, E., Couture, J., Tan, S., Zulla, R. T., & Lam, G. (2013). Education as a social determinant of health: issues facing indigenous and visible minority students in postsecondary education in Western Canada. International journal of environmental research and public health, 10(9), 3908–3929.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph10093908

- UNESCO (2020) Education: From disruption to recovery.

https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse

- UNESCO (2020) Adverse consequences of school closures.

https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse/consequences

- WHO (2020) What we know about COVID-19 transmission in schools

https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/risk-comms-updates/update39-covid-and-schools.pdf?sfvrsn=320db233_2

- WHO (2020) Checklist to support schools re-opening and preparation for COVID-19 resurgences or similar public health crises.

https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240017467

Like what you see? Amplify our collective voice with a contribution.

Got some good news to share? Contact us on our social media pages above.

Return to the main blog page or sign up for blog updates here.

- Log in to post comments