Masks for Fires: Kathryn Conlon, PhD, MPH Analyses new California Emergency Wildfire Smoke Regulation For Outdoor Workers

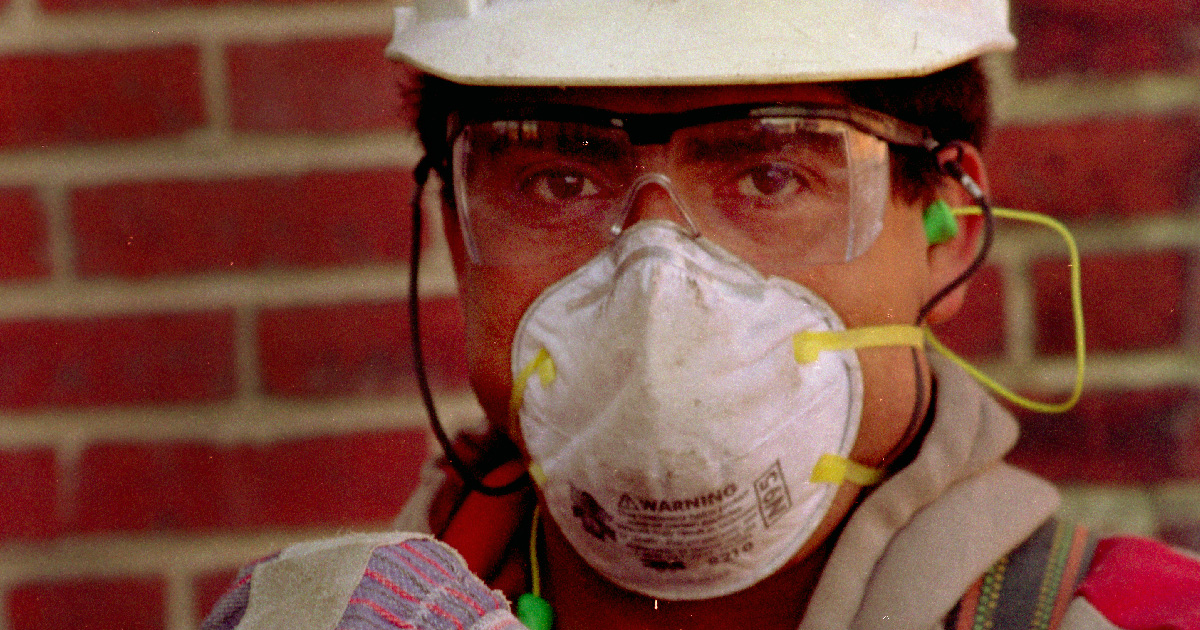

[A construction worker wearing a mask and other protective equipment. Photo by Earl Dotter ]

For two weeks in November, 2018, the California sun was almost extinguished. The Camp Fire, which quickly became the deadliest wildfire in California history, was torching the northern foothill community of Paradise and its small forested neighbors, burning from November 8th to 25th. Massive plumes of smoke from the Camp Fire bore down on Chico, one of the northernmost cities of the Central Valley that acts as a sister town to Paradise, and swept down the entire length of the great valley, smothering the entire San Francisco Bay Area and hundreds of thousands of acres of farmland in the valley. Those seeking to outrun the smoke had to cross the Grapevine, the uphill grade on Highway 5 through the mountains that signifies the southern end of the Central Valley and acts as the mountainous gateway to the sprawling suburbs of Los Angeles. The Grapevine is over 400 miles from Paradise.

Shortly after crossing, however, a new plume of smoke arose: the Woolsey Fire, active from November 8th to 21st, burned down celebrity homes in Malibu and blackened large swathes of the Santa Monica Mountains. Its smoke blanketed the Southern and Central California coast, including miles of farm fields.

These fires were devastating and tragic. But, in addition to those acutely affected by the fires in their hot epicenters, hundreds of thousands of others were affected by the smoke. Throughout the Central Valley and along the California coast, agricultural workers toiled in the smoke, even as the level of particulate matter in the air climbed. The Air Quality Index for much of the Central Valley hovered between “Very Unhealthy,” with fine particle readings (PM 2.5) between 201 and 300 in some regions, and spiking to “Hazardous,” between 301 and 500, in others.

[ Agricultural workers outdoors in heavy smoke during the fires. Photo by Central Coast Alliance United for a Sustainable Economy]

Around this same time, CAUSE (the Central Coast Alliance United for a Sustainable Economy), a nonprofit focused on justice for working families, circulated a photo of agricultural workers working among the rows of silver-grey artichokes in Oxnard, California, a coastal agricultural town outside of Santa Barbara in southern California. The sky behind them is dark blue and faded orange, heavy and ominous from smoke. The workers aren’t wearing masks. Some health advocates in the region reported that their efforts to hand out free N95 masks were rebuked by farm owners, who wouldn’t allow the advocates in the fields. The photo went viral.

“When the air quality is poor, people who work outdoors are still expected to work”, noted Kathryn Conlon, PhD, MPH. She’s an assistant professor in the Department of Public Health Sciences at the University of California, Davis -- in a town that itself was blanketed in Camp Fire smoke last year.

When air quality drops precipitously, public health experts encourage people to find a safe place to breathe. “From a public health standpoint, the first recommendation is to stay indoors, to find a clean airspace. If you can’t be indoors because it’s an older home that is leaky or you don’t have an air purifier, you’re encouraged to go to a place that does, like a mall or movie theater.” Indeed, during the fires, news media, government officials, and common sense encouraged all people to stay indoors. Yet, she notes, when the rest of the population is encouraged to stay indoors or head to the mall, outdoor workers are still in the fields.

In the wake of the Camp Fire, farmworker advocates responded to this discrepancy by calling on California’s Occupational Safety and Health Administration (CalOSHA) to assure that air quality is monitored and outdoor workers are properly outfitted for respirators in the case that air quality is unsafe. CalOSHA quickly responded.

The result is a new emergency regulation that requires employers to provide N95 masks to all outdoor workers when air quality has exceeded 151 on the Air Quality Index, covering the “very unhealthy” category. The regulation assures that agricultural workers, construction workers, and landscaping workers, and even semi-outdoor workers like auto body shops workers or garbage collectors, would be provided a mask when either a worker or an employer confirms that air quality has entered the hazardous designation. An addition, the regulation states that, if a worker has a hard time breathing because of wildfire smoke, regardless of the air quality designation, the worker can request a N95 mask without penalty from an employer. The emergency regulation is in effect until a permanent regulation can be developed and implemented.

“The swift action [by CalOSHA] to respond to a community-driven request to have some health protection was impressive,” she said. “I appreciate that we need to provide some care” to outdoor workers in a fire event. “But we also need to make sure we’re giving evidence-based guidance on how to do that correctly. We still just don’t know how those masks will work in that population.” Data are limited on mask usage while doing hard labor outdoors, often also in the heat. “I wish we had more data. Maybe you can be working outdoors, but maybe only for 90 minutes at a time, without the mask coming off.” In the absence of solid data, Dr. Conlon is very appreciative for CalOSHA’s rapid response, and simultaneously hesitant to firmly support masks during a fire event.

[An N95 mask hanging on a pole. Photo by Kai Hendry. This image is licensed under: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode]

“From the public health standpoint, we need more data about the efficacy of the mask being used in real-world scenarios,” before judging the regulation, she noted. In real world situations, using the mask correctly for hours at a time is unlikely. “Getting the correct protective fit is not always easy, especially if you are moving around a lot. Also, they’re not intended to be work for a very long time -- you’re supposed to throw them out after eight hours of use,” Dr. Conlon noted. “And you are supposed to leave it on your face. If you push it up to your forehead, or down to your chest, which you’re inclined to do if you’re hot or if you want to take a drink, you might lose some protection,” because the fit will no longer be tight when reapplied, she added.

The problem of massive wildfires is not limited to California, with huge fires burning across the Western states, the Midwest, and deep into Boreal zones that once never saw fire. Climate change accelerates forest fires by providing higher temperatures and dryer tinder, adding to the likelihood of large blazes that create hazardous smoke events. Although this regulation is limited to California, many states are considering ways to mitigate the health consequences of more regular and more severe smoke. This emergency regulation can be a test.

Dr. Conlon and others in her field are working on research in this field. “In the lab, you can create an environment to simulate what an exposure might look like in a mask,” she said. “You can do a lot in the lab, but to the extent to which it accurately simulates what happens outdoors, I’m not familiar.” She is hopeful that, as a result of more mask usage during fires, researchers will better understand how effective mask use is at limiting or eliminating smoke exposure in hazardous conditions. Her own research will bring her to work with agricultural workers and owners to assess the practical implications of the new N95 mask rule. Until then, Dr. Conlon encourages clinicians and regulators to shift perspectives.

“[We need] some type of response that acknowledges the expectations that our society has to continue to do that type of work when the work environment is hazardous,” she noted. “I understand not everything can stop, but it is unacceptable for us to expect people to be working hard labor jobs when it’s likely unsafe for their health. If we aren’t able to prove that something like a respirator can protect them, then I think we should be asking ourselves the question, ‘do we really want to put our neighbors at risk?’ … A mindset shift needs to happen.”

Learn more about Dr. Conlon’s research at UC Davis: “Protecting Human Health in a Changing Climate”

Like what you see? Amplify our collective voice with a contribution.

Got some good news to share? Contact us on our social media pages above.

Return to the main blog page or sign up for blog updates here.

- Log in to post comments