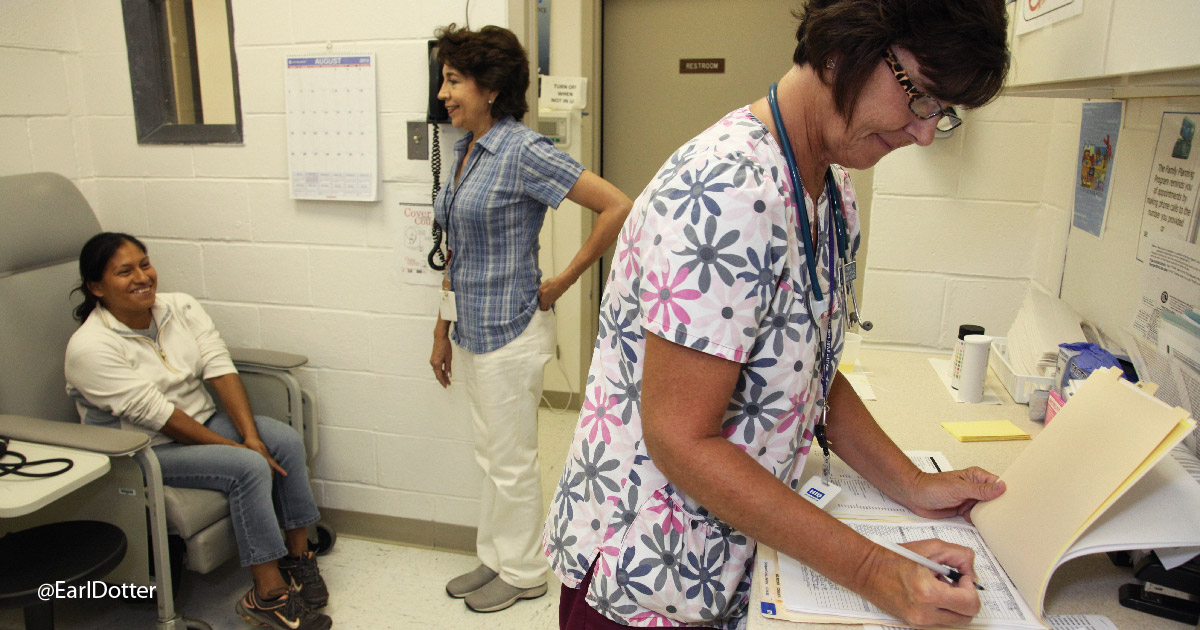

photo courtesy of Viriginia Garcia Memorial Health Center

Patients are increasingly mobile. From an agricultural worker who moves with the seasons, to a businessperson who visits clients around the globe, to a recent immigrant, to a young woman who recently returned from a honeymoon abroad, the next patient in the exam room is highly likely to have recently experienced some level of mobility, or will in the near future. Mobility complicates care -- but it doesn’t need to interrupt it. The most valuable and powerful diagnostic tool in our current medical toolbox to bring us to the correct diagnosis for our increasingly global patient populations is one of the most basic: the taking of a patient’s medical history.

CONFHER Model

The CONFHER model is a cultural assessment tool to guide clinicians to gather the most pertinent information during patient intake. Here’s a brief summary of the questions one could ask when using the model.

Communication: What is her preferred language in which to communicate? What non-verbal cues is she using, like eye contact or body language?

Orientation: What is the patient’s ethnic identity? When asked, where does he consider home?

Nutrition: What kinds of foods does the patient prefer, and do they have any effect on treatment? For example, the patient may have gastrointestinal distress, and only eats spicy foods.

Family relationships: Does the patient have control over treatment decisions? Does another member of the family make medical decisions for the patient?

Health beliefs: How is the patient experiencing her illness? How does it affect her life? Does the patient’s religion or culture inform how the patient responds to or communicates about her illness? For example, in some cultures, illness may be seen as a punishment that the patient must suffer through due to past transgressions.

Education: What is the patient’s education level? If the patient is no- or low-literacy, what health education may he need? For example, an agricultural worker may apply pesticides but not be able to read warning labels.

Religion: How do the patient’s religious or spiritual beliefs or preferences affect her life and her relationship to Western medicine?

Medical history-taking is an art form, and nowhere does it require so much skill and dexterity as with a patient from another culture, who may be more comfortable in a language other than the clinician’s, or who has been recently mobile. Each of those aspects -- culture, language, and mobility -- require careful consideration while taking a medical history.

Culture

“Cultural humility” or “cultural sensitivity” continue to be important components for clinicians to embody in the exam room. But what do they entail? They start with a basic understanding that we come to the clinic with our own ideas, experiences, and biases which may be different or at odds with our patients’. Our ideas and biases could potentially lead us in the wrong direction when we take a history. Make sure you go through all the steps without assumptions -- don’t let your preconceptions make the diagnosis.

Clinicians can learn some of the cultural characteristics, history, values, belief systems, and behaviors of the more common ethnic groups among the clinician’s community to develop sensitivity to their needs. This doesn’t mean expert level understanding or full integration -- just basic familiarity. One clinician serving a large Ethiopian refugee community commented that just saying a few key phrases of greeting in her patients’ language sets her patients at ease, as they recognize the clinician reaching out to the patient -- even if they don’t share the same language. On my trips to rural Guatemala and Honduras, I found it a bit strange when new patients would ask me, the clinician, personal questions at the start of an exam, such as if I had a wife or children at home, until I saw that having a basic level of understanding of my lifestyle and value system opened a level of trust that I didn’t have with them when they first arrived, and helped the patients connect with me across cultures, which made easier the next step of taking a patient history. I recognized the cultural cue instead of brushing it off. Don’t dismiss one culture’s norms; if a traditional healer’s approach is not detrimental to my treatment strategy, I won’t discourage the patient from going to the healer as well.

I have learned to treat patients the way they wish to be treated, not the way that I wish to be treated. Such careful attention to the patient allows a clinician to successfully navigate many different cultures even without extensive background in each one. Another part of cultural sensitivity is understanding that, even with familiarity, there is cultural diversity between and within cultures. Again, self-awareness that our assumptions should not be the main guide will help us assure that the patients are the guide.

Learning to read the situation, listening, and asking more open-ended questions if confused can expose culture-related conflicts or help you catch cultural cues you may have otherwise missed. Listening includes reading body language. If you see hesitancy or annoyance, you may be running into a intercultural misunderstanding. The best reaction may be to pause and simply ask the patient if they are worried or concerned about something. Ask questions to understand what things mean in their culture. Open-ended questions allow the patient time and space to tell their story, in their own words. Here are some example questions:

What do you think is causing your illness?

Do you have an explanation for why it started when it did?

What have you done to treat this?

What does your sickness do to you -- how does it work?

Have you asked anyone else to help you?

What kind of treatment do you think you should receive?

Language

Asking such questions can be challenging if the patient doesn’t speak the clinician’s primary language well. Interpreters are a must in a clinic, either an on-staff interpreter that is available for the appointment or interpreters through a phone-based interpretation service. Here are some interpretation tips:

- Family members -- and especially children -- should never be used for interpretation.

- Avoid slang or jargon and speak directly to the patient, not to the interpreter or phone.

- If you have an interpreter in the room, start with some ground rules. Ask the interpreter to repeat back everything the patient says, and if the interpreter would like to add any cultural interpretation, to do so after repeating word-for-word what the patient said.

- Pay attention to how a patient responds to a question -- body language, force of words, other non-verbal cues -- by always focusing your attention on the patient.

- Have the interpreter sit next to and a bit behind the patient, so that the path between you and the patient is clear.

- Make sure you look ahead at your schedule at least one day (or much longer for a less common or an American Sign Language interpreter) to assure that you have the interpreters on hand for the appointment.

- Ask patients to repeat your treatment instructions. If they use the same words, they may not have fully understood. Rephrase, and ask them to restate the instructions.

Remember that even if you have a brochure in the patient’s preferred language, the patient may not be able to read it, or read it well. Literacy level is another consideration as you navigate global patients.

Mobility

Travel history is too often left out of a patient history. With our globalized world, a patient may arrive in your office just days after being in a rural part of the other side of the world. During the Ebola crisis, we had signs put up in all of our clinics asking patients to tell us if they had recently been to West Africa; during the Zika crisis, the signs asked about the Caribbean. Most of these signs have come down, but we still need to know where patients have been. Ask patients if they have recently traveled, if they plan to travel, and if anyone in their household has had recent illness as well, to determine if someone else’s travel may have affected your patient. The patient may have contracted his disease in transit, as well, so be sure to understand the method and route of travel. Occupation can uncover additional details that may lead you to a diagnosis; mobile agricultural workers, for example, often work out-of-doors during the day, with limited to no health education, access to preventative care or even basics that can help prevent illness like water, shade, insect repellent, window screens, or sunscreen. A patient who is a truck driver might say he has not been traveling, as he associates “traveling” with “vacation,” not with his daily grind.

Simple awareness, good questions, and lots of attention to the patient can oftentimes bring a correct diagnosis just from the medical history -- and it doesn’t have to be costly. Although it may require a few more minutes of a clinician’s time, it is significantly less expensive than an MRI or other expensive diagnostic test. With a good medical history, the clinician should have the ability to construct a reasonable differential diagnosis list that then can limit the number of diagnostic tests needed to confirm or rule out each diagnosis entertained. As our world continues to shrink, and technology has made movement faster and easier, the least technologically advanced tool -- a patient history -- has become all the more important.

Learn more at MCN’s archived webinar, “Treating Global Health At Your Doorstep Starts with a Good Patient History,” at https://goo.gl/hiqRKW.

The material presented in this portion of Streamline is supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) under cooperative agreement number U30CS09742, Technical Assistance to Community and Migrant Health Centers and Homeless for $1,094,709.00 with 0% of the total NCA project financed with non-federal sources. This information or content and conclusions are those of the author and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsements be inferred by HRSA, HHS or the U.S. Government.

Read this article in the Summer 2018 issue of Streamline here!

Sign up for our eNewsletter to receive bimonthly news from MCN, including announcements of the next Streamline.