Since 2018, Migrant Clinicians Network (MCN) has offered a Spanish-language series on Type 2 Diabetes for community health workers (CHWs), patient navigators, patient advocates, case managers, and outreach workers, who support the health of migrant and immigrant farmworkers, and factory, construction, and service industry workers. The six-session virtual series follows an ECHO model, a learning framework developed by the University of New Mexico that they call “all teach, all learn” – meaning, a highly participatory environment that invites the participants to share case studies and best practices, instead of leaning solely on an instructional, expert-centric approach. MCN’s Diabetes ECHO may have been the first Spanish-language ECHO in the nation, tailored to a critical member of the care team who frequently lacks access to expertise. “Most CHWs or promotores do their work within their communities, and rarely have the opportunity to speak with an expert, which may be even more true for those working in rural areas or in rural health centers,” due to their remoteness, noted Martha Alvarado, Program Manager of Online Education and Evaluation for MCN. “To be able to access such expertise is really a gift that I'm sure a good majority would never be able to access with confidence and in the language that is most understood by them.”

Just as critically, “the participants not only get to know MCN, but also each other,” said Alvarado, who is the primary coordinator of the series and co-host alongside Lois Wessel, DNP, FNP-BC, an assistant professor at the Georgetown University School of Nursing and an active clinician serving migrants, immigrants, and refugees. “Let’s say someone from a health center in Puerto Rico is struggling with a patient, we may have another promotora from Washington who is having the same issues. Participants compare notes and ask each other how to handle a situation or proceed with a patient.” This collaborative learning process helps develop community and partnerships but also enables the spread of promising practices.

Additionally, Alvarado and Wessel, aided by expert guest speakers, provide participants with a deep clinical understanding of diabetes “so they can have that conversation with a clinician who is going to speak to them with [clinical] terms” in English, but also the duo gives them tools so they can talk plainly and effectively with neighbors and community members in Spanish, Alvarado said. The series presents strategies, information, and resources to bolster efforts to prevent diabetes, recognize cases, and support newly diagnosed patients. Topics include motivational interviewing, diet and lifestyle, diabetes among children and adolescents, diabetes and mental health, self-management of diabetes, diabetes during a disaster, and more, incorporating up-to-date research and strategies that are culturally relevant for and applicable to the wide range of Spanish-speaking communities across the country.

This year’s ECHO Diabetes Series featured the most diverse group of participants yet, in terms of country of origin. Seven countries, along with the US and Puerto Rico, were represented by the 24 participants who provided information. In previous years, the participants were mostly from Mexico; this year, for the first time, Mexicans made up less than half. “I believe it’s a reflection of the communities they serve,” and a growth of the CHW model into more and more communities, said Alvarado. “Now, their communities have someone with knowledge, who can say, ‘this is what you’re experiencing, it could be this or that.’” Latin America is diverse; many communities have distinctive cultural and even linguistic differences over short distances, Alvarado added. To successfully engage a community in changing habits to improve health, she added, trust is critical. “And if you have someone who looks like you and talks like you, it will be easier to break through.”

To match the diversity of participants, the ECHO series seeks a diversity of experts. Every week, the session includes experts from universities, government agencies, community organizations, health centers, or elsewhere, to answer questions, provide fresh perspectives and approaches, and complement the conversations of participants around the many aspects of diabetes affecting their community’s health. MCN is seeking to expand its panel of diabetes experts. Please contact Martha Alvarado, malvarado@migrantclinician.org, to learn more about the opportunity to share your expertise during our 2024 Diabetes ECHO series.

MCN’s Diabetes Comic Book, Updated for Puerto Rico

Spanish speakers in the United States are not a monolith – and the population is changing. As of 2020, over 62 million people in the US identify as “Hispanic or Latino.”1 While people with Mexican heritage still account for more than half of this population, increases in immigration from Central and South America and the Caribbean have diversified communities around the country. For example, between 2000 and 2020, people of Venezuelan descent in the US grew 550%, a percentage that has continued to grow since then due to instability in that country. Over those 20 years, the number of people of Paraguayan, Honduran, and Guatemalan descent in the US each increased by over 300%.2 An estimated 5.6 million people of Puerto Rican descent live in the US – compared to the 3.4 million living in Puerto Rico today.3 This makes people of Puerto Rican descent the second largest population of Latinxs in the US, behind only people of Mexican descent.

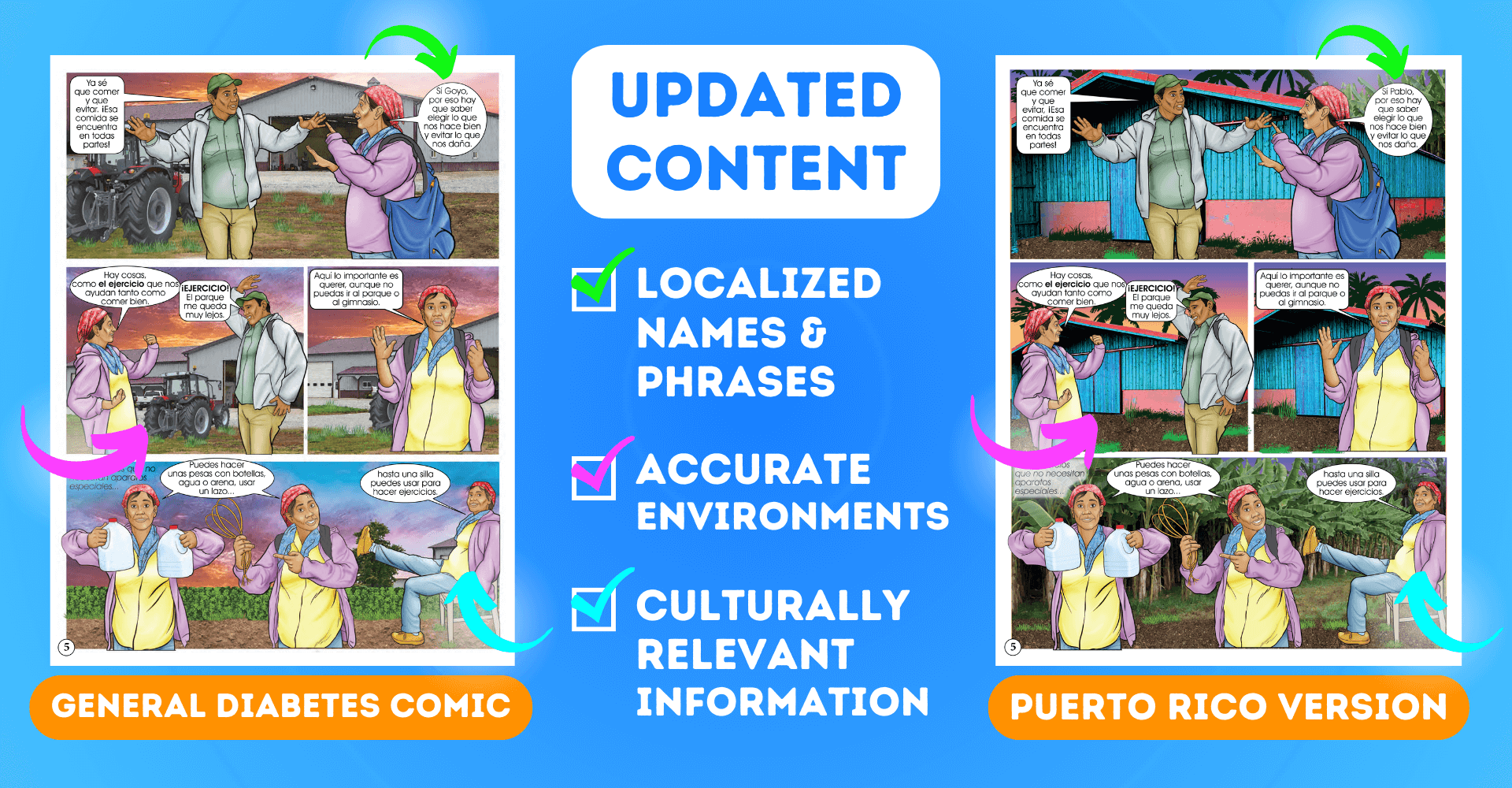

Community health workers are tasked with building trust with and meeting the health needs of their diverse Spanish-speaking communities. Recognizing the need for more culturally attuned resources, Migrant Clinicians Network recently released a new version of the diabetes comic book, Mi salud es mi tesoro or My Health is My Treasure, redesigned to better reflect the culture and diet of Puerto Ricans.

Changes include name changes, emphasis on Puerto Rico activities and preferences, and brighter colors and Caribbean scenery throughout. Soccer is swapped out for dancing and basketball; a piñata is replaced with dominos; a coffee carafe becomes a moka pot preferred in the Caribbean. The food choices and sample menus have also been altered to reflect more typical Puerto Rican foods. Yucca, yams, and pumpkin are favored over corn tortillas; concha pastries become donuts.

“With the help of a cadre of Puerto Rico nutritionists and people living with diabetes, MCN carefully reviewed and adapted content and menus to reflect Puerto Rico conditions, language, and food practices so the comic book will be appropriate for people living with diabetes on the island. We aim for useful and resourceful educational materials, where the community feels identified and with concepts and words that make sense and are easy to follow,” said Alma Galván, MHC, Director of Community Engagement and Worker Training for Migrant Clinicians Network, who oversaw the redesign along with Salvador Saenz, illustrator, Jose Rodriguez, MD, and MCN’s Puerto Rico team. “Alianza Nacional de Centros de Salud Comunitaria, Inc. understands how useful this tool will be for CHWs in Puerto Rico -- they will sponsor a printing so that all 12 health centers in Puerto Rico can use it. This will be a powerful tool for CHWs to help people better understand their diabetes and how to manage it.”

Access the diabetes comic book’s three versions, English, Spanish general, and Spanish Puerto Rico, on our diabetes comic book page: https://www.migrantclinician.org/resource/my-health-my-treasure-guide-living-well-diabetes-comic.html

Diabetes & Mental Health

Migrant Clinicians Network’s Diabetes ECHO has one session exclusively dedicated to mental health. “Especially since COVID, I think many of [the CHW participants] have felt the weight of having to deal with the pandemic on top of the already difficult job of providing education and care to their communities,” Alvarado said. Consequently, the session addresses not just mental health and well-being for their patients, but also for themselves. The session provides numerous resources and basic education, but also, a needed outlet, “to let them get all that off their minds in a healthy way that allows them to reflect and understand the emotions they are feeling and how to best address them,” Alvarado said. Some of the key areas discussed:

Diabetes Distress: Anxiety, fear, frustration, sadness, exhaustion, and stress around the daily management of diabetes has its own name – diabetes distress. These emotions may arise when a patient has been trying to manage their diabetes but isn’t seeing results or feels limited in life by their illness. Many factors may bring on diabetes distress: changing food choices, taking medicines daily, checking blood sugar levels, clinical check-ups, and shame are called out in the 2023 Diabetes ECHO training. The CDC estimates that during any 18-month period, 33 to 55% of people with diabetes will experience diabetes distress.4 People experiencing this distress may turn to a CHW or outreach worker who is accessible to the patients, trusted by the community, able to speak in the language of the patient, and familiar with and considerate of cultural aspects of these health concerns, so these clinicians must be well equipped to respond with empathy and encouragement – and an action plan.

Two-Way Relationship: Depression, stress, and anxiety may impact an individual’s ability to keep up with their diabetes management. Simultaneously, diabetes and related health issues and risks may increase anxiety and stress or worsen depression, leading to a two-way relationship between the two conditions. Additionally, the profile of people with diabetes who may struggle with depression is different from the overall population. About 17% of people of Latin American origin have diabetes in the United States, compared to just 8% of the white population. Certain heritages within the “Hispanic” umbrella are at even more risk. Puerto Ricans, for example, have significantly higher rates of diabetes.5 While fewer people of Latin American origin report symptoms of depression compared to the overall population, depression is on the rise, particularly among young people of Latin American origin.6 Factors relating to culture, immigration status, and acclimation may further increase risk of depression. Stigma exists around both depression and diabetes in many of these communities.7

Referring Patients for More Care: Participants are instructed to refer the patient to a mental health professional if: 1) There is any possibility of the patient harming oneself or others; 2) The patient ignores their diabetes self-management; 3) Stress is affecting the work-life-health balance; 4) Severe mental illness is apparent; and 5) There are signs of an eating disorder.

Self-Care: Participants are taught numerous tactics to relieve or manage stress that they can then share with their patients or use for themselves. Social support, community, and medication are strongly featured as key protective elements of mental health for patients with diabetes.

Diabetes during COVID: The series focused on the health needs of patients – but, necessarily, the mental health needs of the participants were also spotlighted. To be able to take care of patients, participants needed to take care of themselves. They reported that the COVID pandemic pressurized their work, with increased needs of patients; fears and reality of infection; the impact of the pandemic on the daily lives of community members from lockdowns, school closures, layoffs, and unsafe workplaces; the rapidly changing COVID situation matched by rampant misinformation among community members; and much more changed the dynamics of their relationships with community members and forced non-COVID health needs into the background. “It's been a struggle trying to do Diabetes Work within the dark shadow of the pandemic,” Alvarado admitted, and COVID has necessarily been woven into the diabetes ECHO series. This was particularly apparent during the mental health session, where space was provided for participants to talk through frustrations around misinformation, patient denial, and the cutoff from patients during lockdown, Alvarado said.

Resources:

Finally, participants are equipped with numerous Spanish-language resources to further support their work with diabetes patients around mental health and well-being. Here are some of the resources shared:

The American Association of Diabetes Educators has numerous Spanish-language resources. Access all of them at; https://www.diabeteseducator.org/living-with-diabetes/spanish-resources. Here is a selection provided during the training:

Diabetes y depression: Doble problema https://www.diabeteseducator.org/docs/default-source/living-with-diabetes/tip-sheets/healthy-coping/depresion_esp.pdf?sfvrsn=d266b458_14

Estrés: Un poquito para todos nosotros https://www.diabeteseducator.org/docs/default-source/patient-resources/tip-sheets/mental-health/estres_esp.pdf?sfvrsn=4

References:

1 Jones N, Marks R, Ramirez R, Ríos-Vargas M. Improved Race and Ethnicity measures Reveal U.S. Population Is Much More Multiracial. United States Census Bureau. 12 August 2021. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/08/improved-race-ethnicity-measures-reveal-united-states-population-much-more-multiracial.html

2 Zong J. A Mosaic, Not a Monolith: A Profile of the U.S. Latino Population, 2000-2020. UCLA Latino Policy & Politics Institute. 26 October 2022. https://latino.ucla.edu/research/latino-population-2000-2020/

3 Noe-Bustamante L, Flores A, Shah S. Facts on Hispanics of Puerto Rican origin in the United States, 2017. Pew Research Center. 16 September 2019. https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/fact-sheet/u-s-hispanics-facts-on-puerto-rican-origin-latinos/

4 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Mental Health. Last reviewed 15 May 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/managing/mental-health.html

5 Johnson JA, Cavanagh S, Jacelon CS, Chasan-Taber L. The Diabetes Disparity and Puerto Rican Identified Individuals. Diabetes Educ. 2017;43(2):153-162. doi:10.1177/0145721716687662 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28112033/

6 Latinx/Hispanic Communities and Mental Health. Mental Health America. https://www.mhanational.org/issues/latinxhispanic-communities-and-mental-health

7 Washburn M, Brewer K, Gearing R, Leal R, Yu M, Torres L. Latinos' Conceptualization of Depression, Diabetes, and Mental Health-Related Stigma. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2022;9(5):1912-1922. doi:10.1007/s40615-021-01129-xhttps://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8432279/