Partnerships between health systems including community health centers (CHCs) and community-based organizations (CBO) have emerged as a promising strategy to improve health outcomes, especially in communities where access to health care may be limited. These partnerships aim to extend the reach of CHCs by linking them together with local organizations. There is plenty of evidence that these partnerships can boost access to critical preventative care like cancer screenings and vaccines—but whether they work well for all members of the community often comes down to how they connect with the communities they are trying to serve.

A recent national study by Cheon and You examined the impact of hospital–community partnerships on preventive health care services across over 3,700 US counties.1 Their findings showed that these types of partnerships are associated with higher rates of mammography screenings and flu vaccinations. However, the benefits of these partnerships were not experienced equally across all communities. Some groups saw significant improvements, while others saw little to no change in outcomes. This shows that just having a partnership is insufficient. The community members’ specific needs must be at the center of these partnerships.

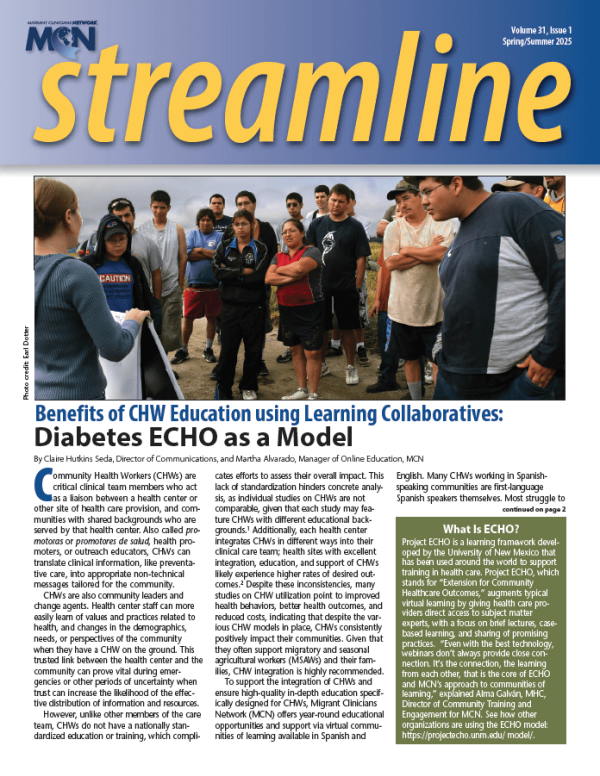

One approach that continues to stand out as a bridge between CHCs and the communities they serve is the integration of community health workers (CHWs). These are “trusted members of the community who are trained to empower their peers through education and connections to health and social services.”2 CHWs play a critical role in translating and sharing health information in ways that reflect empathy and a deep understanding of the everyday realities of those they serve.

Their work goes beyond sharing facts—it fosters meaningful knowledge-sharing within communities. As Bhowmick et al. point out, when health information is exchanged between peers, neighbors, and family members, it becomes more than just data; it becomes a shared community resource.3 CHWs are essential to this process. They do not just distribute pamphlets or explain clinical procedures. They create space for sensitive health topics to be discussed in ways that are respectful, relatable, and tailored to the community’s values. By doing so, they help clinics deliver care that is not only more effective, but also more comprehensive and has the community in the center.

ACEs Aware is a California statewide effort to improve health outcomes through a person-centered approach to care. It is grounded on the understanding that adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) can be key drivers of leading health issues, like diabetes, heart disease, and kidney disease. It is the first effort in the nation to screen patients for ACEs to help improve health outcomes and save lives. ACEs Aware not only invested in equipping clinicians with the education and training to conduct ACE screenings but also ensured that a significant amount of the initiative’s resources are available for use at the community level, proving clinics and communities can come together to co-create meaningful, community-focused care.

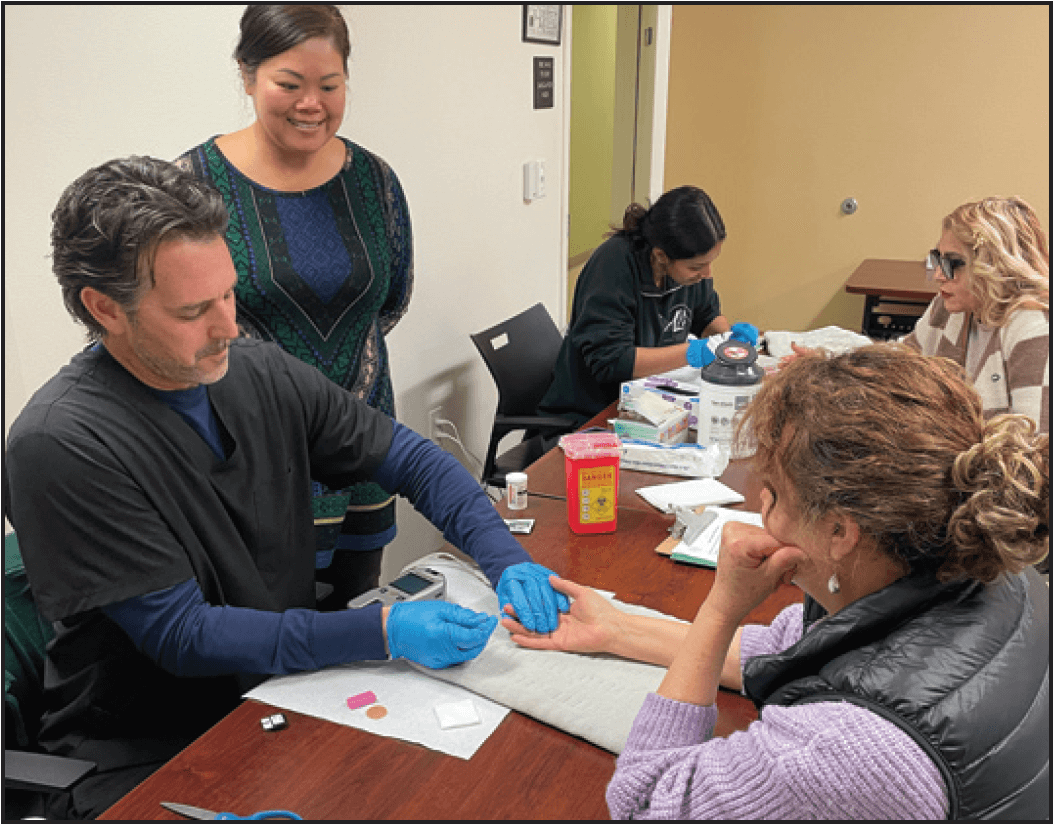

Funded through this initiative, the NACES project (No more Adverse Childhood Experiences) is a great example of what this can look like in action. The project brought together clinics and community-based organizations including Lideres Campesinas and Alianza Nacional de Campesinas to co-design a model for addressing ACEs in rural migratory and seasonal agricultural worker (MSAW) communities.4 It used a dual-intervention model that included a community-based component where MSAW leaders were trained to deliver peer education trainings, and a clinic-based component that trained clinicians and staff on ACEs and person-centered care.

On the community side, MSAW leaders received training not only in ACE content, but they also strengthened their skills in teaching, facilitating group discussions, referring community members to resources, and documenting outcomes.5 Our evaluations show that MSAWs who participated in their peer-led trainings walked away with a better understanding of ACEs, more willingness to seek care at community health centers, and a stronger sense of how to take care of their own mental and emotional well-being. Many also expressed a strong desire to continue learning about mental health, a topic that comes with stigma in many communities. They also offered clear, concrete feedback on how clinics could better serve them: extend clinic hours, improve language access, train staff to better understand MSAW realities, and provide ongoing education about mental health and health care navigation.

On the clinic side, NACES improved readiness across participating clinics. Staff felt more confident discussing ACEs and reported positive changes in clinical practices, though barriers like time constraints and staff turnover still remained. One important success was that separating ACE education from screening helped foster trust and more honest disclosures from patients.

The NACES pilot project demonstrated that introducing sensitive topics through trusted community members—who embody empathy and a deep understanding of the contextual realities of the community—can have a profound impact. Partnerships with community-based organizations like Líderes Campesinas to deliver health education not only enhances patient understanding and engagement but can also support clinics in providing more effective and comprehensive care.

Citations

1 Cheon O, You NY. Effectiveness of Hospital-Community Partnerships in Preventive Health Care Interventions: An Exploration of Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Impact. Health Equity. 2025;9(1):8-17. Published 2025 Jan 8. doi:10.1089/heq.2023.0259

2 “Who Are Community Health Workers?” MHP Salud. https://mhpsalud.org/our-programs/community-health-workers/

3 Bhowmick A, van der Zande MM, Harris R. Knowledge-seeking and knowledge sharing of health services across social networks and communities: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2025;25(1):443. Published 2025 Mar 27. doi:10.1186/s12913-025-12525-y

4 Estrada-Darley I, Alvarado G et. al. Addressing Adverse Childhood Experiences in Clinics Serving California Farmworker Communities: NACES Pilot Project Evaluation. RAND. 31 July 2024. Available at: https:/www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA2152-2

5 NACES Pilot Project Report. Migrant Clinicians Network. May 2024. Available at: https://www.migrantclinician.org/resource/naces-no-more-adverse-childhood-experiences-pilot-project-report.html?language=en